- Home

- Sandra Cisneros

Martita, I Remember You/Martita, te recuerdo

Martita, I Remember You/Martita, te recuerdo Read online

Sandra Cisneros

Martita, I Remember You

Sandra Cisneros was born in Chicago in 1954. Internationally acclaimed for her poetry and fiction, which has been translated into more than twenty-five languages, she is the recipient of numerous awards, including the National Medal of the Arts, the PEN/Nabokov Award, and a fellowship from the MacArthur Foundation. Cisneros is the author of The House on Mango Street, Caramelo, Woman Hollering Creek, My Wicked Wicked Ways, Loose Woman, Hairs/Pelitos, Vintage Cisneros, Have You Seen Marie?, A House of My Own, and Puro Amor, a bilingual story that she also illustrated. Cisneros is a dual citizen of the United States and Mexico and makes her living by her pen.

www.sandracisneros.com

Also by Sandra Cisneros

Have You Seen Marie?

Caramelo

Woman Hollering Creek

The House on Mango Street

Loose Woman (poetry)

My Wicked Wicked Ways (poetry)

Hairs/Pelitos (for young readers)

Vintage Cisneros

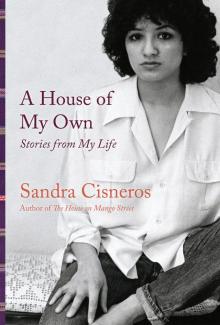

A House of My Own

Puro Amor

A VINTAGE CONTEMPORARIES ORIGINAL, SEPTEMBER 2021

Copyright © 2021 by Sandra Cisneros

Translation copyright © 2021 by Liliana Valenzuela

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Vintage Books, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and distributed in Canada by Penguin Random House Canada Limited, Toronto.

Vintage is a registered trademark and Vintage Contemporaries and colophon are trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Cisneros, Sandra, author. Valenzuela, Liliana, translator.

Title: Martita, I remember you = Martita, te recuerdo / Sandra Cisneros ; traducido por Liliana Valenzuela.

Description: New York : Vintage Books, 2021.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021005550 (print) | LCCN 2021005551 (ebook)

Classification: LCC PS3553.I78 M3718 2021 (print) | LCC PS3553.I78 (ebook) | DDC 813/.54—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021005550

Vintage Contemporaries Trade Paperback ISBN 9780593313664

Ebook ISBN 9780593313671

Cover design by Perry De La Vega

Cover photograph © Elliot Erwitt/Magnum Photos

Author photograph © Keith Dannemiller

www.vintagebooks.com

ep_prh_5.7.1_c0_r0

Contents

Cover

About the Author

Also by Sandra Cisneros

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Martita, I Remember You

Martita, te recuerdo

Acknowledgments

To Susan Bergholz

and

for Dennis Mathis

and Robin Desser

Most Saturdays you can find me in the dining room with my scraper and blowtorch, once the kitchen is clean and the girls are at the library. In 88 BC, Mithridates, king of Pontus on the Euxine, was at war with Rome…Xenophon. Things bubble up from I don’t know where inside me, like the sticky layers of varnish I’m attacking with the propane torch.

* * *

The varnish peels off in stubborn ribbons, a practice in patience. I’ve got no right to complain. It was my idea to strip the wood instead of paint. Every Chicago apartment I’ve ever lived in has a dining-room hutch like ours built into one wall wearing a hundred and six years of varnish like layers of honey-drenched phyllo.

* * *

In 88 BC, Mithridates, king of Pontus…and then I have to put my scraper down, shut the torch valve, and poke around the winter closet, past house contract and birth certificates and property tax files, searching for you in letters spilling photos; a scalloped paper napkin; postmarks from France, Argentina, Spain; tissue envelopes with striped airmail borders, the handwriting tight and curly like your hair.

* * *

And it’s as if we’re talking to each other, still, after all this time, Martita.

Querida Puffina:

I don’t know if I was the one who didn’t answer your letter or if you were the one who didn’t answer mine. It no longer matters.

* * *

I was rearranging my dresser, and in a drawer I found your letters. (I hope the address is still the same.) Then everything came back, that New Year’s Eve in Paris, more than that, a feeling, a sentiment—I don’t have a good memory, but I do remember emotions.

* * *

How many days did we know each other? I don’t even know. But I know I grew to love you very much, Puffina. That’s what I felt, all at once, when I found your letters.

* * *

I wanted you to know it. That’s all. I have a photo of us—you and me and Paola—taken in the metro in one of those automated booths. Remember? I’m happy to have it.

* * *

To try to tell you what’s happened to me since then is difficult—

* * *

I was at the point of marrying, but it couldn’t be. It’s just been a little while since I broke it off, and I’m a little sad. It will pass.

* * *

In May I’m going back to Europe to avoid our Argentine winter. I’ll be in Madrid. Here’s the address in case you’re still traveling:

Marta Quiroga Pascoe

A/A Irene Delgado Godoy

Villanueva y Gascón no. 2–3a

28030 Madrid

España

* * *

I don’t know how long I’ll stay there. Maybe I’ll return soon to Buenos Aires. Maybe not. I have to restructure my life a bit. I’ve made a bit of a mess of it. God willing, I’ll hear some bit of news from you. Don’t forget me.

I hug you,

Marta

* * *

Ay, Martita, it’s been how many years since you wrote that? Ten? Fifteen? I haven’t forgotten you. Not once. Those letters between us, pebbles tossed into water. The rings growing wide and wider.

* * *

Rereading your letter this morning, it seems strange to hear myself called Puffina again. After so much time. I don’t know where I left Puffina. Paris? Nice? Sarajevo? So much has happened since then.

* * *

I still have my copy of that photo, the one you mention, from the Les Halles métro. All of us squeezed into the booth, sticking our tongues out, crossing our eyes, Paola pugging her nose like a pig. Three poses for ten francs. One for you, one for me, one for Paola. Paola treated us, remember?

* * *

We’d been Christmas shopping at the Galeries Lafayette. All afternoon looking and looking at pretty things.

* * *

Just as we were leaving, the store detectives leapt out before the revolving doors. The three of us hustled to the stairwell, shoppers staring with their mouths open like fish.

* * *

In the basement, a crowded wood-paneled office with a two-way mirror. Slumped in a chair crying and crying, someone’s granny with hennaed hair. What had she taken? A chandelier? Where did she hide it, I wondered.

* * *

I remember bei

ng cocky mad because I didn’t know about Paola yet. Everything from my pockets on the desk, as ordered. My métro carte Sésame tickets. Wrinkled Kleenex. The fluorescent-pink notepad I bought at Monoprix. Two purple felt-tip pens. The key to the boys’ apartment in Neuilly-sur-Seine. My wallet with all my French money, paper and coin. The American passport—I made sure they saw that.

* * *

You didn’t even blink when Paola pulled three pairs of gloves from her pocket like a string of paper dolls. Three cheap woolen pairs with the price tags on them—a beige pair, an olive, a red.

* * *

They let us go with a warning and ugly words thudding at our backs.

* * *

When we’re walking to the métro, Paola says, —Oh, I am so shameful, Puffina. Not for me, but for you and Marta. Swear, Puffi, you will never tell anyone about this. Promise me, I beg of you.

* * *

—I promise, I say.

* * *

Then, as if to make it all better, Paola treated us to the portraits.

* * *

That’s the only photo I have of us, Marta, can you believe it? The one we took after they threw us out of the Galeries Lafayette. When I got home to Chicago and had my photos developed, all my Paris rolls were blank. Not a single frame. Not the morning we went to visit you in Saint-Cloud, not the Café Deux Magots, not the New Year’s Eve party, not the goodbye at the Gare de Lyon.

* * *

We were waiting for something to happen. Isn’t that what all women do until they learn not to? We were waiting for life to sweep us up in its arms—a Strauss waltz, a room at Versailles flooded with chandeliers. Paola waiting for that job, not just any job, not as an au pair or a salesgirl, but one that would keep her from having to return to her uncle’s house outside Milano.

* * *

Me, I was waiting for a letter from an arts foundation in the Côte d’Azur, for my life to begin. All my earnings from my summer job at the gas company disappearing. My room in a pension near the Place de la République, a former broom closet behind the reception desk, just wide enough for a bed like a train berth. Down the hall, a tiny shared shower with a water heater that gobbled up francs, the money I’d saved for my classes going down the drain.

* * *

A tingle in my chest when I gave it any thought.

* * *

But I couldn’t go home, I couldn’t. Not until I could call myself a writer.

* * *

And you, Martita. What did you want? Just to be able to say, when you returned to Buenos Aires, —Paris? Oui, oui. Je suis la mademoiselle Quiroga s’il vous plaît, s’il vous plaît, bonjour, madame, merci.

* * *

All good Argentines know Paris is the center of the universe. Je suis la mademoiselle Quiroga. Bonjour, madame. S’il vous plaît.

* * *

J’ai vingt ans. I’m twenty years old. J’ai faim. I’m hungry. J’ai froid. Froid, froid. I’m cold. Cold, cold. J’ai peur. I’m frightened. Avez-vous faim? Vous avez faim? Are you hungry? Vous avez peur? Are you frightened? J’ai mal au coeur. I’m sick from the heart. J’ai très peur. I’m very frightened.

* * *

Bravo, Martita. We’re so proud of your French. You talking to your mama from the broken pay phone that lets us all call home for free. Every Latin American in Paris lined up and waiting to say, —Próspero Año Nuevo. Bonne nuit. I miss you. Please don’t cry. Merci beaucoup. Te quiero mucho. Bonsoir. It’s cold, cold.

* * *

We wait our turn and watch you show off your bird-whistle French to your mama in Buenos Aires. —Bonjour, madame Quiroga—. That pretty profile of yours, half of an algebraic parenthesis. —Bonjour, madame—. Martita chirping like a native.

* * *

Paola has a little snippet of a nose, too, like yours, but she had to pay for hers.

* * *

—What do you think Paola looked like before?

* * *

—I don’t know. I didn’t know Paola with her old nose.

* * *

Paola, Martita, and me walking down the Champs-Élysées arm-in-arm, the way women walk together in Latin America to tell men we are good girls, stay away, leave us the hell alone.

* * *

—Corina, sing the Puffi song—Paola commands—. Per favore.

* * *

—But you know it better than I do—I say—. I don’t even know what I’m singing.

* * *

—Please, Corina, sing—Marta says.

* * *

And I sing the song Paola taught me, as if I am her trained parrot, without understanding the words and with the ones I do know all crooked and in the wrong place. It makes Paola laugh to hear me sing that cartoon jingle. And now, because I sing it on command, she insists on calling me Puffina instead of Corina. She says I’m tiny, like the Puffi characters, the height of two apples.

Chi siano non lo so

Gli strani puffi blu

Son alti su per giù

Due mele o poco più

* * *

Martita and Paola, suntanned and pretty. A tabby kitten and a golden Palomino. I meet them at la peña, the Latin American party at 1 rue Montmartre, ground floor, rear. A damp room, taller than it is wide, stinking of smoke, mold, red wine, sewage, and patchouli. Silvio Rodríguez from a tape deck. Lights covered with gels, and our faces glowing red like a poster by Toulouse-Lautrec. People seated on every space, including the floor. You have to be careful not to step on anyone.

* * *

—This is Marta and this is Paola.

* * *

Who introduces us? The Peruvian musicians? The boys from Neuilly?

* * *

—This is Marta and this is Paola.

* * *

At first I call Marta Paola, and Paola Marta.

* * *

—Paola?

* * *

—No, I’m Marta, she’s Paola.

* * *

The schoolgirl in the plaid coat with a hood is you, Marta. From Buenos Aires. A scribble of auburn curls hiding a face flecked with freckles. Eyes transparent as pearl onions. A laugh you cover with your hands, as though your teeth were crooked when you were little.

* * *

The bossy filly in tweed and a fedora, our Paola, ready to break into a run. Bottle blond with a mane she keeps flicking over her shoulder so people will think she’s classy. A northern Italian with the river Po in her eyes, woolen greens and muddy browns speckled with amber.

* * *

And me? I cut my hair as short as a boy’s as soon as I arrived in Paris. I wear a rooster-feather earring and a long scarf wrapped twice around my neck like the locals, but it’s no use. I still look like what I am. A bird who forgot how to fly.

* * *

Martita, you talk to me in that Spanish of the Argentines, the sound tires make on streets after it’s rained. Paola speaks Spanish and English and Italian all at the same time, jumbled words flying like sparks, the syllables jerked without warning.

* * *

—Did you just come from the coast?—I ask, because you’re both so glamorously tanned.

* * *

—We were in Geneva for the skiing—Paola says before you can answer, and you look at each other and laugh.

* * *

It isn’t until after la peña when we’re waiting for the métro that Marta tells me, —That story we told you earlier about skiing, that isn’t true. We work at a tanning salon. We just tell the skiing story so people will think we’re rich.

* * *

There’s a hole in my heart, as if someone had taken a cigarette and pushed it right through, clear to the other side. What began as a pinprick is now big enough to push a finger through. When it’s damp out, it pinches the same as these shoes I paid too much for in the Latin Quarter.

Have You Seen Marie?

Have You Seen Marie? Woman Hollering Creek: And Other Stories

Woman Hollering Creek: And Other Stories The House on Mango Street

The House on Mango Street A House of My Own: Stories From My Life

A House of My Own: Stories From My Life Loose Woman

Loose Woman Caramelo

Caramelo Martita, I Remember You/Martita, te recuerdo

Martita, I Remember You/Martita, te recuerdo A House of My Own

A House of My Own My Wicked Wicked Ways

My Wicked Wicked Ways