- Home

- Sandra Cisneros

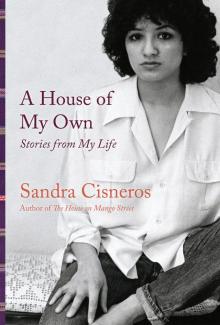

A House of My Own: Stories From My Life Page 2

A House of My Own: Stories From My Life Read online

Page 2

My destination of choice was Patagonia, the tip of South America, with a plan to work my way north to Buenos Aires, home of all things I loved—the tango, Borges, Storni, Puig, and Piazzolla. But how could I manage it? The idea of traveling through Latin America was too overwhelming for a woman who’d never traveled alone outside of the States. And to make things worse, I knew the local men would think I was inviting their company just by traveling solo. Overwhelmed, I convinced myself it would be easier if I deferred Patagonia till I was a more seasoned voyager.

Luckily, earlier in the year I’d met Ifigenia, a poet of Greek descent. Ifigenia was going to Athens to visit family that fall, and she said I could tag along. We made plans to meet in September in Athens. This was a relief to me since I had nightmares that combined my greatest fears. I dreamt of being locked in a dark room with a ghost mouse. With Ifigenia alongside me, I felt calmer.

I have a vague recollection of sending a “My dog ate my homework” letter to my small-press publisher who was waiting for the promised manuscript by summer’s end. What else could I do? There was no refund on my ticket to Greece. I flew away and tried not to think about him too much. He had an infamous temper.

I went to Athens first, staying with Ifigenia at her parents’ home, a pristine apartment that smelled deliciously of moussaka. We poked around town seeing the requisite antiquities, and then off we went to Piraeus to visit the islands—actually only one, in the end, though we arrived with the original agenda of seeing others.

Hydra was where we went, because it was said to be full of artists, and Hydra was where we stayed, because it was heaven. We rented rooms in funky pensions and did the things writers do on Greek islands—sit under the awnings of outdoor cafés scribbling in journals, eating calamari, and making friends with the town’s outrageous citizens. When we were done attracting eccentrics, we returned to Athens, where an angry letter from my publisher was waiting for me. I can’t remember what it said, but if it was a cartoon, I would draw smoke coming out of the envelope. It was enough for me to realize I wasn’t going anywhere till I finished that book.

The delay of my book made it impossible for me to keep my promise to my Chicago nemesis; we had planned to rendezvous in Morocco. I wrote and said I wasn’t coming, and the reply was a sirocco of rage. I was writing my book, I couldn’t come, but it was useless to explain. I was miserable. I’d chosen my writing over a man. It wouldn’t be the last time.

And so we went back, Ifigenia and I. To live on Hydra instead of just visit. An island only a few hours from Athens, close enough to the Peloponnesus you could see it across the horizon.

In the beginning we lived near the horseshoe port with its day divided by boat whistles. “Here we are!” Or, “We’re off!” Each letting us know the time of day without looking at a watch. Day tourists tumbled off huge ocean liners and took the same pictures of tavernas, flowered archways, and donkeys before climbing back on board and dashing away.

On our first Hydra visit we’d met two Greek-Egyptian brothers who had a shop at the far end of the harbor next to the café that sold paninis. Konstantinos and Vasilis Embiricos. They owned an odd gift shop filled with fur coats and cheap plaster imitations of Greek antiquities, a strange combination of dusty merchandise, made all the more bizarre by the sweltering autumn heat.

I liked the brothers Embiricos, and they liked me. Vasilis, the pudgy elder, looked like the film noir actor Peter Lorre, the same wide forehead, oily hair, and huge froggy eyes clogged with sorrow, as if they’d seen too much for one lifetime. He was divorced, separated, widowed? I can’t remember. He was alone and lonely. Konstantinos, on the other hand, was as lean as a Giacometti, a striking man with a lovely little boy who lived in Athens with his mother. They weren’t millionaires, indebted as they were to their expired alliances and the children these had produced. They lived on an interior street in modest houses they most likely rented and did not own, bright on the outside but dark as caves on the inside. Their street, like most streets on the island, was meticulously neat, with the cobblestones in front of their house scrubbed daily by fanatic Greek housewives.

When I was searching for lodgings, Konstantinos offered me his home, which unfortunately came with Konstantinos. For the short time I lived there I enjoyed how the mornings entered, the pleasure of admiring the light on the ceiling with its luster of a polished dime.

Then Konstantinos grew too fond of me, and I searched for a house of my own. I took the first one shown, at the top of the mountain, practically where civilization ended and wilderness began. (Ifigenia joined me in the beginning, but the stairs eventually defeated her. I counted over three hundred and fifty steps from the port to my door. In the end she found writing in the cafés more to her liking and moved into lodgings near the port.) I signed a two-month lease for two hundred dollars a month, the same amount as the rent on my Chicago Bucktown flat, handing back the keys the morning I finished The House on Mango Street, November 30, 1982.

The Hydra house was a simple summer cottage. Like all Greek houses, it was whitewashed inside and out with lime each Easter. It had a high garden wall, thick walls, gentle lines, and rounded corners, as if carved from feta cheese.

From the upstairs bedroom window you felt you could leap and soar over the town, a geometry of sparkling sugar cubes that tumbled toward the sea. On the opposite shore lay a mirage of land called the Peloponnesus with its hazy mountain range, and above all this, a great indulgence of sky. The famous light of Provincetown had nothing on Greece. This was splendid, eternal, serene.

Our village was built like the amphitheaters of antiquity, entirely of stone. Every sound could be heard by every neighbor, whether it was a porcelain filtzanaki cup set back on its china saucer or a radio blasting Giorgos Salabasis’s big hit of that season, “S’agapao m’akous” (“I Love You, Do You Hear Me?”).

In the beginning, while the early October days were still warm, I set up my office in the garden under a canopy of grapevines dizzy with drunken bees. I borrowed Konstantinos’s French typewriter, whose keys were set up differently than an English keyboard, and everything I typed that season—story, poem, letter—came out with the same consistent typing errors.

When I lifted my head from the page, the mountains across the mainland were a sun-faded lavender like vintage velvet ready to dissolve into dust. Each day the sea a different shade of blue than the day before, and each shade of blue contrasting with those other strips of blue—sky and mountains.

One of the great delights of my Hydra house was pulling open the bedroom windows each morning, twin doors of three panes each, unlatching the shutters, a rattle and moan, a slight shove, and they would swing and open like arms spread out wide to belt out a song: sea, sky, garden pouring in. S’agapao m’akous!

The house, its windows and the joy of opening them: they found their way into my novel in the vignette “Sally” (or the vignette found its way into reality). Because my house was like the one the protagonist Esperanza dreams about, with windows that let in plenty of blue sky.

Once, at this same bedroom window I caught with my hands what I thought was a huge moth, but between its fluttering I could see it was a velvety bird or bat or some other mythical creature halfway between insect and sprite. I let it go, too frightened to get a better look.

While living in the Hydra house, I had this dream. I dreamt I was swimming with the dolphins in the Aegean. We leapt in and out of the water joyously like a needle stitching the sea. This was all the more remarkable because in real life water terrifies me.

Living on Hydra was like this, somewhere between reality and the imagination. I lived a life enchanted and watched myself living this enchanted life tap-tap-tapping on a typewriter in a beautiful house with a view of the sea like the writers in movies.

I wanted to share my good luck and immediately invited all my friends and family to join me. But no one took me up on the offer. “Good lucky,” as my mother might’ve said, or I would’ve never finished my book.

I had two months to work.

I worked best at home and preferred to come down to the port only when I needed groceries, which was almost daily since I wasn’t much of a cook. I woke at noon, strapped on the leather sandals I’d bought from the shoemaker at the port, and ran down to town two steps at a time, hurrying before the shops closed for lunch and their leisurely siesta.

At the harbor I’d buy cucumbers and yogurt and garlic to make tzatziki. I’d buy eggs for breakfast. I’d buy olives scooped out of a barrel with oil and wrapped in a twist of wax paper and a thick slice of sopping feta cheese. Then on the way back up the mountain I’d stop at a little shop crowded with patrons eating standing up like horses, and there I’d make my last purchase, a bit of grilled lamb for my dinner.

There was water all around us, but there were no fish. The waters had been fished clean, Konstantinos explained. I did venture out once with him to fish for calamari one night but never again. To witness the calamari gasping in our boat after we’d caught them was too much for me and made me cry. But it wasn’t enough to stop me from enjoying them the next day with olive oil and lemon.

Near Konstantinos’s house there was a bakery that sold delicious spinach-cheese pies that I bought hot from the oven along with fresh loaves of bread I’d slice and wedge with Swiss chocolate bars. I weighed 118 pounds then and must’ve burned the calories climbing the three hundred and fifty steps up to my house. How else to explain this miracle?

The cost of living on Hydra was high for the locals because practically everything was imported, including drinking water. Even though the island’s name meant “water,” this was just a memory from centuries before when Hydra once boasted several natural springs. Hydra had no water left, just like the sea had no more fish. It had to import its supply from the mainland, as it did just about everything else, including the meager produce. Sad oranges, bruised apples, a few cucumbers, maybe onions. Going to the market felt as if we were living in times of war, but now in retrospect it may have been that way only for me, the one who woke at noon and had to make do buying the dregs.

There was only one vehicle on Hydra, a huge truck that hauled off the garbage to some remote part of the island, a place that scared me when I thought about it. Our island existed only for the self-centered port and the nearby hippie village of Kaminia, with great bluffs between the two towns that looked down into water flooded with schools of dangerous jellyfish.

At night I worked on the kitchen counter because a hanging lamp above was the only proper lighting in the house. If I’d had a good workday, I’d go down into the port afterward to meet Ifigenia, or to dine with Konstantinos at a taverna, or at his brother Vasilis’s house because Vasilis liked to cook, or to dance at a disco, or to have an ouzo at a bar after a day of channeling stories.

Though I enjoyed company, I was happiest when I stayed aboard my own landlocked ship, content to admire the world from that remote vessel called home. I would linger at my bedroom window like Penelope awaiting her Odysseus, the garden overflowing with grapes, plumbago, and jasmine on one side, and on the other the busy port bobbing with ocean liners, humble fishing boats, and millionaire yachts.

My house was just a cottage, yet it was the most beautiful place I’d ever lived, then or since. I mooned over it like a lovesick teenager, and the house absorbed my adoration. In the day I left the double doors and the windows open, the light as soft as a pearl, the house full of wind. Cement sinks and floors, exposed plumbing, banquettes built into the wall, a rudimentary kitchen with a camping cooktop fueled by a tank of propane. Nothing fancy. Someday I will have a house just like this, I told myself. Its simplicity gave me infinite pleasure, and this pleasure allowed me to write.

Hydra, Hydra, Hydra! A flag flapping in the wind. I loved its intimacy. I could walk everywhere. I loved the privacy of its high walls. I sat at my bedroom window with one leg indoors and one leg out, as if straddling a great white winged horse, admiring both the interior and exterior worlds at once.

I was at home. I considered even staying forever. But I couldn’t reason how. I was not Greek. I would have to learn an entirely new culture. These were not my people, not my cause. And how would I earn my living? Ah, if only…, I thought to myself.

Was it true there were as many chapels on the island as there were days of the year? I don’t know. But there were enough miracles, or so it seemed to me. Once Konstantinos plucked a jasmine flower from a vine and gave it to me, and I was as astonished as if he’d pulled a rabbit from a hat. I had no idea jasmine grew on walls. I’d never seen a jasmine flower till that night, white as the moon, milky and sweet.

The wondrous thing about the island was that there was no way for a criminal to get away. I could walk home alone at night without fear. Everybody knew who you were and where you were going, and could stop you before you left the island. Whether this sense of safety was true or not, it was a novel feeling for me as a woman and as a Chicagoan. I’d never felt like this before and seldom have since.

—

The greatest marvel of all, I wrote every day, or at least that’s how I remember it. I wrote in longhand and then typed what I’d written, wrote corrections over my typed text until I couldn’t understand the knotted string called my handwriting. Then I’d type the page clean again from the beginning, a process that repeated itself over and over, and which I enjoyed, because it allowed me to hear the text, like a composer listening to music inside his head.

Where are those sheets of paper now? I wonder. Probably in the Hydra garbage pit, a place of horrors, I imagine, overrun with giant rats on the far side of the island, every bit as squalid as the other side was glamorous.

Was I reading during this time? I can’t imagine otherwise. I know I had a paperback copy of The Necessity of Art: A Marxist Approach by Ernst Fischer, which I tried to finish to impress my Chicago nemesis, but there are passages underlined only in the early chapters, though I carried the book around with me through Greece, Italy, France, Spain, and Yugoslavia, trying to appear intelligent. I remember none of it.

The tavernas were democratic agoras where the rich and the not-so-rich crossed paths. I recognized the colossal head of Ted Kennedy in the taverna where I was having lunch one rainy afternoon with Konstantinos and Vasilis. Ted and company had stepped off a sparkling yacht and were busy chewing on the same greasy potatoes and overcooked chicken as we were.

The island boasted handsome stone mansions built by millionaires, old sea captains, and, rumor had it, pirates, ancient and modern. They certainly looked like they’d taken a treasure to build. Who these wealthy were, I never knew. Everyone sitting at the cafés looked as affluent or poor as everyone else. In that sense it appeared an egalitarian society, though we knew that wasn’t true.

Credit 1.5

To live on an island with land in sight is calming. Huge liners slid into the port depositing their day tourists. Hydrofoils hovered above the water speeding to and from Piraeus like nervous dragonflies. Our harbor stank of cat urine, dead fish, seaweed, retsina. All the while the sound of water constantly sloshing against the mossy stone walls of the port. The Greek men tossing their kompoloi, worry beads, loafing all day long at the cafés, eyed the fresh crop of foreign women in scanty summer wear trotting off the boats, while the Greek women, Greek tragedies of their own making, were more industrious than worker ants, cleaning, always cleaning, their task, like that of Sisyphus, never ending.

We watched hoteliers hovering about the incoming tourists as soon as they stepped off the boat plank, hoping to lure them to their lodgings. And nobody intervened to warn the young girls in backpacks about the pension near the clock tower whose owner was a notorious peeping Tom. No matter. They’d find out soon enough.

The Greeks had a nonverbal language I had to learn to decipher. When they flicked their head and ticked with their tongue after you asked them a question, it didn’t mean “What a stupid question!” but simply “no.” And when they shouted when they spoke to you, you learned not to take

it personally. This was the usual tone they used when talking to one another.

It was while living on Hydra that I realized the Greek women had the same sad hoarse voices as the seagulls. I imagined they had metamorphosed like in a tale by Ovid. They were the most beautiful women I saw in Europe, with agate eyes, lovely beings even with their harsh voices. But their beauty spoiled too quickly, while the men’s charms endured.

Because ours was an island without vehicles, there was no way to lug things uphill except by hand or by donkey. The routes the animals took were littered with fresh dung. The men who herded these beasts spoke a donkey language made up of sounds like “brrrr,” and tongue ticks like the one that meant “no,” and shouts I hoped the donkeys learned not to take personally, but it seemed they did. They were sensitive creatures who cried with their heads thrown back to the sky. Pobrecitos.

Since there were no street names on Hydra when I lived there, to give an address you had to take someone by the hand, or give very specific directions: “Do you know the house with the wall with the double-headed eagle? Take a left there and go up and up following ‘Donkey Shit Lane,’ you can’t miss it, follow their trail, and then when you get to an overpass covered with jasmine, the second house on the right, by the olive tree. That’s where I live.”

—

There was a woman from Germany on the island I’ll call Liesel. She had worked with the famous directors from the New German Cinema—Fassbinder, Herzog, Wenders. Liesel lived in a beautiful house with several terraces where the mountain refused to budge. It made for a magical experience entering that house with its high whitewashed walls and olive and lemon trees and bougainvillea, its rooms sparsely but beautifully decorated with items dragged with great effort from Vienna or Cusco. Every object in Liesel’s house looked like it was ready for its close-up—a wooden bucket sitting under a brass garden spigot, an antique bentwood bed in the center of an empty room, a kitchen basket dangling from a wooden ceiling beam with a hairy rope.

Have You Seen Marie?

Have You Seen Marie? Woman Hollering Creek: And Other Stories

Woman Hollering Creek: And Other Stories The House on Mango Street

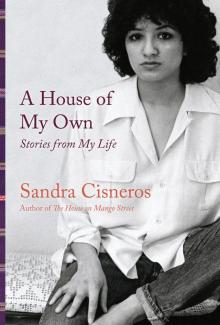

The House on Mango Street A House of My Own: Stories From My Life

A House of My Own: Stories From My Life Loose Woman

Loose Woman Caramelo

Caramelo Martita, I Remember You/Martita, te recuerdo

Martita, I Remember You/Martita, te recuerdo A House of My Own

A House of My Own My Wicked Wicked Ways

My Wicked Wicked Ways