- Home

- Sandra Cisneros

My Wicked Wicked Ways: Poems Page 3

My Wicked Wicked Ways: Poems Read online

Page 3

She lived mistress.

Died solitary.

There is as well

the cousin with the famous

how shall I put it?

profession.

She ran off with the colonel.

And soon after,

the army payroll.

And, of course,

grandmother’s mother

who died a death of voodoo.

There are others.

For instance,

my father explains,

in the Mexican papers

a girl with both my names

was arrested for audacious crimes

that began by disobeying fathers.

Also, and here he pauses,

the Cubano who sells him shoes

says he too knew a Sandra Cisneros

who was three times cursed a widow.

You see.

An unlucky fate is mine

to be born woman in a family of men.

Six sons, my father groans,

all home.

And one female,

gone.

OTHER COUNTRIES

And at times we feel a little like exiles; a woman feels like that when she does not live up to the image of her required by the times, when she does not interpret it, and hence searches for paths, for other “countries” where life for her will be different from that in her own country, in the homeland given her by her mother’s womb.

—MARIA ISABEL BARRENO, MARIA TERESA HORTA, AND MARIA VELHO DA COSTA, THE THREE MARIAS

Letter to Ilona from the South of France

for Ilona Den Blanken Nesti

Ilona, I have been thinking

and thinking of you since I went away,

dragging you with me across the South of France

and into Spain. Then back again.

I ran away to an island off the coast,

tiny jewels of fields beneath the jewel of sky—

and lost myself one night in crumpled poppies.

Odd for such a city poet like me

to find such comfort in the dark—

I who always feared it—and yet

I loved the way it wrapped me like a skin.

All those stars, Ilona. And wind.

Field illumined by those poppies.

Yes, that was good.

I wanted to bring that back forever,

wrap it in a velvet cloth to show you.

The wind from Africa. The field of poppies.

The way my bicycle hummed the distance.

And for me, Ilona, who has never known

the liberty of darkness, who has never

let go fear, how do I explain a joy this elemental,

simple like your daughter’s hand outlined in crayon.

And yet I think you understand

my first sky full of stars—

you who are a woman—

the wind from Africa, the field of poppies,

the night I let slip from my shoulders.

To wander darkness like a man, Ilona.

My heart stood up and sang.

Ladies, South of France—Vence

At 4 P.M. the promenade begins.

The wives who walk with husbands

and the ones without

who do not walk at all.

They gather like dusty birds

beneath their paisley

and polka-dot

and plaid and blue-checked

and yellow and plum-colored

parasols.

And in their penny-whistle French

each evening when the sunlight dims,

they sing.

December 24th, Paris—Notre-Dame

The Seine runs along.

Merrily, merrily.

The river. The rain.

Water into water.

A blue umbrella fading into fog.

A child into his mother’s arms.

Buttresses leaping delirious.

Wind through the vein of trees.

The rain into the river.

Tomorrow they might find a body here—

unraveled like a poem,

dissolved like wafer.

Say the body was a woman’s.

Ophelia Found.

Undid the easy knot and spiraled.

Without a sound.

A year ends

merrily. Merrily

another one begins.

I go out into the street once more.

The wrists so full of living.

The heart begging once again.

Beautiful Man — France

I saw a beautiful man today

at the café.

Very beautiful.

But I can’t see

without my glasses.

So I ask the woman next to me.

Yup, she says, he’s beautiful.

But I don’t believe her

and go to see for myself.

She’s right.

He is.

Do you speak English?

I say to the beautiful man.

A little, the beautiful man says to me.

You are beautiful, I say,

No two ways about it.

He says beautifully, Merci.

Postcard to the Lace Man—The Old Market, Antibes

To tell the truth,

I can’t remember your name.

It’s those Catalán eyes

I can’t let go of.

That and the memory

of an inky tea

sweetened with orange water,

the sticky perfume

of a cigarette

from Persia,

those photos of Tangiers.

I forgot to tell you.

I have a great respect

for wives.

Especially yours.

Au revoir, mon ami.

C’est la vie.

That afternoon

at the Musée Picasso—

a pretty memory and enough

for me.

Letter to Jahn Franco—Venice

You were full of stories.

Was that red jacket of yours really

once Bob Marley’s?

The man you live with actually

your brother?

Those three women from Valencia

all your lovers?

It doesn’t matter.

Venice was a good adventure.

Dancing through canals.

Ducking bridges from a motorboat

that sped delirious at 4 a.m.

under a laughing moon.

So I let you down.

Didn’t give in and fall

under the spell of a bona fide

Venetian artist on the street,

replete with easel. A modern

Casanova—wow.

I remember that pathetic last ciao

you gave me at the railway station—

you said you felt as if

you’d bought an ice-cream cone

and it had fallen to the ground

before you had a chance to taste it.

Bought.

Always that metaphor somehow or other.

And what was I

except an item not for sale.

Well.

After all, a man invests his time,

his money even,

though this was fifty-fifty.

I owed nothing.

Tell me,

one artist to another,

what does a woman owe a man,

and isn’t freedom what you believe in?

Even the freedom to say no?

At least you did the night before

when we clinked our glasses to the Muses

and our common god.

I don’t know.

For all that talk of liberation

I still felt that seam of anger

when I danced with you

and sometimes not with you at all.

What if I hadn

’t gone home alone?

Say my eye had gotten tangled with another’s.

Or maybe yours.

It might’ve happened that way.

You never know.

But to tell the truth

I think true nature rises

when the body dances.

Perhaps that’s why I never

have one partner,

prefer to dance alone.

No, I won’t

come to Sardinia with you.

Or even Spain.

The truth is that uncomfortable next morning

we had nothing to say to one another.

Hardly a word until we reached the station.

An ice-cream cone.

In case you change your mind, you said.

I know you won’t, but just in case,

I’ll wait in Venice seven days.

You were right about one thing—

I didn’t come back.

To Cesare, Goodbye

Cesare,

with those Medici eyes

you could go far

I said.

But you’ve never

been away from Tuscany

except for a cousin’s wedding

in Milano.

I said come with me to Spain.

Spain you said and laughed.

Too far away—

even Rome is too expensive.

You were waiting for

that job at the post office,

a letter from an uncle

that might help.

Maybe one day

I will see you in America

I said.

Maybe

you said.

And laughed.

Ass

for David

My Michelangelo!

What Bernini could compare?

Could the Borghese estate compete?

Could the Medici’s famed aesthete

produce as excellent and sweet

as this famous derriere.

Did I say derriere?

Derriere too dainty.

Buttocks much too bawdy.

Cheeks so childishly petite.

Buns, impudently funny.

Rear end smacking of collision.

Ah, misnomered beauty.

Long-suffering

butt of jokes,

object of derision.

Pomegranate and apple

hath not such tempting

allure to me

as your hypnotic

anatomy.

Then

am I victim

of your spell,

bound since mine eyes

did first espy

that paradise of symmetry.

And like Pygmalion transfixed,

who sincere believed

desire could unfix

that alabaster chastity,

grieved the enchantment

of those small cruel hips—

those hard twin bones—

that house such enormous

happiness.

Trieste—Ciao to Italy

for Natale Mancari

Maybe we should’ve fallen in love.

Or pretended to be.

What was there to lose

except a few hours of sleep.

You needed me.

But that wasn’t reason enough.

And love is no charity,

no tin cup and yellow pencils.

What did we expect?

Trieste was full of disappointments—

a town that got lucky and had the sea.

And how could I explain in raggedy Italian

I still liked you.

Maybe when your train gets into Milano

and mine to Dubrovnik, we’ll perhaps regret

what didn’t happen. Maybe.

But any town with a name

this sad deserves nothing

but a stony memory.

Peaches—Six in a Tin Bowl, Sarajevo

If peaches had arms

surely they would hold one another

in their peach sleep.

And if peaches had feet

it is sure they would

nudge one another

with their soft peachy feet.

And if peaches could

they would sleep

with their dimpled head

on the other’s

each to each.

Like you and me.

And sleep and sleep.

Hydra Night—House on Fire

When houses burn here

you just watch.

There is nothing

but the sea

for irony.

Cinders wild as flies.

Rooster crowing day too early.

Night illumined. Moonless sky.

I worked with others

dragging furniture outdoors—

books, tables, lamps—

to save what could be saved.

Water drizzled from a skinny hose.

Buckets passed from

hand to hand to hand.

Somebody cursed in Greek.

A neighbor gave me her sweater,

asked if I was cold.

First the grape arbor came down.

And then the windows spoke.

We watched until the roof

sighed twice, then died.

Then one by one went home

to dream of fire.

Hydra Coming Down in Rain

I’m not certain

but I imagine even

mountains melt.

In Hydra

they come down

in rain

and down

on cobbled

steps

inside your shoes

unless your boots

are rubber

red.

Bleed

from lemon trees,

whitewashed walls,

wooden shutters,

gravel,

bougainvillea,

clay tile roof,

pomegranate,

copper gutter,

slippery flagstones,

fresh donkey shit,

and jasmine flowers.

Down and down

until the mountain

meets the port

and spills

into

the sea.

Fishing Calamari by Moon

for A. Stavrou

At the bullfights as a child

I always cheered for the bull,

that underdog of underdogs,

destined to lose, and I tell you

this, Andoni, so you’ll understand,

though we are miles from bullrings.

The Greek moon a lovely thing

to look at above our boat.

We are an international crew tonight.

Greek sea, African Queen, you, me.

But I am sad. Probably the only

foolish fisherman to cry

because we’ve caught a calamari.

You didn’t tell me how

their skins turn black

as sorrow. How they suck the air

in dying, a single terrifying cry

terrible as tin.

You will cook it in oil.

You will slice it and serve it

for our lunch tomorrow.

Endaxi—okay.

But tonight my heart

goes out to the survivors,

to the ones who get away.

To all underdogs everywhere,

bravo, Andoni. Olé.

Moon in Hydra

Women fled.

Tired of the myth

they had to live.

They no longer wait

for their Theseus

to rescue, then

abandon them.

Instead,

they take

the first boat out

to Athens.

Live alone.

No longer Hydra women

bound to stone.

Smoke rises

from the Athens shore,

and some say

it’s the fumes of autos,

motor scooters,

factory pollution.

But I think

it’s an ancient rage.

Women who grew tired

beneath the weight of years

that would not buckle,

break nor bend.

One Last Poem for Richard

December 24th and we’re through again.

This time for good I know because I didn’t

throw you out—and anyway we waved.

No shoes. No angry doors.

We folded clothes and went

our separate ways.

You left behind that flannel shirt

of yours I liked but remembered to take

your toothbrush. Where are you tonight?

Richard, it’s Christmas Eve again

and old ghosts come back home.

I’m sitting by the Christmas tree

wondering where did we go wrong.

Okay, we didn’t work, and all

memories to tell the truth aren’t good.

But sometimes there were good times.

Love was good. I loved your crooked sleep

beside me and never dreamed afraid.

There should be stars for great wars

like ours. There ought to be awards

and plenty of champagne for the survivors.

After all the years of degradations,

the several holidays of failure,

Died solitary.

There is as well

the cousin with the famous

how shall I put it?

profession.

She ran off with the colonel.

And soon after,

the army payroll.

And, of course,

grandmother’s mother

who died a death of voodoo.

There are others.

For instance,

my father explains,

in the Mexican papers

a girl with both my names

was arrested for audacious crimes

that began by disobeying fathers.

Also, and here he pauses,

the Cubano who sells him shoes

says he too knew a Sandra Cisneros

who was three times cursed a widow.

You see.

An unlucky fate is mine

to be born woman in a family of men.

Six sons, my father groans,

all home.

And one female,

gone.

OTHER COUNTRIES

And at times we feel a little like exiles; a woman feels like that when she does not live up to the image of her required by the times, when she does not interpret it, and hence searches for paths, for other “countries” where life for her will be different from that in her own country, in the homeland given her by her mother’s womb.

—MARIA ISABEL BARRENO, MARIA TERESA HORTA, AND MARIA VELHO DA COSTA, THE THREE MARIAS

Letter to Ilona from the South of France

for Ilona Den Blanken Nesti

Ilona, I have been thinking

and thinking of you since I went away,

dragging you with me across the South of France

and into Spain. Then back again.

I ran away to an island off the coast,

tiny jewels of fields beneath the jewel of sky—

and lost myself one night in crumpled poppies.

Odd for such a city poet like me

to find such comfort in the dark—

I who always feared it—and yet

I loved the way it wrapped me like a skin.

All those stars, Ilona. And wind.

Field illumined by those poppies.

Yes, that was good.

I wanted to bring that back forever,

wrap it in a velvet cloth to show you.

The wind from Africa. The field of poppies.

The way my bicycle hummed the distance.

And for me, Ilona, who has never known

the liberty of darkness, who has never

let go fear, how do I explain a joy this elemental,

simple like your daughter’s hand outlined in crayon.

And yet I think you understand

my first sky full of stars—

you who are a woman—

the wind from Africa, the field of poppies,

the night I let slip from my shoulders.

To wander darkness like a man, Ilona.

My heart stood up and sang.

Ladies, South of France—Vence

At 4 P.M. the promenade begins.

The wives who walk with husbands

and the ones without

who do not walk at all.

They gather like dusty birds

beneath their paisley

and polka-dot

and plaid and blue-checked

and yellow and plum-colored

parasols.

And in their penny-whistle French

each evening when the sunlight dims,

they sing.

December 24th, Paris—Notre-Dame

The Seine runs along.

Merrily, merrily.

The river. The rain.

Water into water.

A blue umbrella fading into fog.

A child into his mother’s arms.

Buttresses leaping delirious.

Wind through the vein of trees.

The rain into the river.

Tomorrow they might find a body here—

unraveled like a poem,

dissolved like wafer.

Say the body was a woman’s.

Ophelia Found.

Undid the easy knot and spiraled.

Without a sound.

A year ends

merrily. Merrily

another one begins.

I go out into the street once more.

The wrists so full of living.

The heart begging once again.

Beautiful Man — France

I saw a beautiful man today

at the café.

Very beautiful.

But I can’t see

without my glasses.

So I ask the woman next to me.

Yup, she says, he’s beautiful.

But I don’t believe her

and go to see for myself.

She’s right.

He is.

Do you speak English?

I say to the beautiful man.

A little, the beautiful man says to me.

You are beautiful, I say,

No two ways about it.

He says beautifully, Merci.

Postcard to the Lace Man—The Old Market, Antibes

To tell the truth,

I can’t remember your name.

It’s those Catalán eyes

I can’t let go of.

That and the memory

of an inky tea

sweetened with orange water,

the sticky perfume

of a cigarette

from Persia,

those photos of Tangiers.

I forgot to tell you.

I have a great respect

for wives.

Especially yours.

Au revoir, mon ami.

C’est la vie.

That afternoon

at the Musée Picasso—

a pretty memory and enough

for me.

Letter to Jahn Franco—Venice

You were full of stories.

Was that red jacket of yours really

once Bob Marley’s?

The man you live with actually

your brother?

Those three women from Valencia

all your lovers?

It doesn’t matter.

Venice was a good adventure.

Dancing through canals.

Ducking bridges from a motorboat

that sped delirious at 4 a.m.

under a laughing moon.

So I let you down.

Didn’t give in and fall

under the spell of a bona fide

Venetian artist on the street,

replete with easel. A modern

Casanova—wow.

I remember that pathetic last ciao

you gave me at the railway station—

you said you felt as if

you’d bought an ice-cream cone

and it had fallen to the ground

before you had a chance to taste it.

Bought.

Always that metaphor somehow or other.

And what was I

except an item not for sale.

Well.

After all, a man invests his time,

his money even,

though this was fifty-fifty.

I owed nothing.

Tell me,

one artist to another,

what does a woman owe a man,

and isn’t freedom what you believe in?

Even the freedom to say no?

At least you did the night before

when we clinked our glasses to the Muses

and our common god.

I don’t know.

For all that talk of liberation

I still felt that seam of anger

when I danced with you

and sometimes not with you at all.

What if I hadn

’t gone home alone?

Say my eye had gotten tangled with another’s.

Or maybe yours.

It might’ve happened that way.

You never know.

But to tell the truth

I think true nature rises

when the body dances.

Perhaps that’s why I never

have one partner,

prefer to dance alone.

No, I won’t

come to Sardinia with you.

Or even Spain.

The truth is that uncomfortable next morning

we had nothing to say to one another.

Hardly a word until we reached the station.

An ice-cream cone.

In case you change your mind, you said.

I know you won’t, but just in case,

I’ll wait in Venice seven days.

You were right about one thing—

I didn’t come back.

To Cesare, Goodbye

Cesare,

with those Medici eyes

you could go far

I said.

But you’ve never

been away from Tuscany

except for a cousin’s wedding

in Milano.

I said come with me to Spain.

Spain you said and laughed.

Too far away—

even Rome is too expensive.

You were waiting for

that job at the post office,

a letter from an uncle

that might help.

Maybe one day

I will see you in America

I said.

Maybe

you said.

And laughed.

Ass

for David

My Michelangelo!

What Bernini could compare?

Could the Borghese estate compete?

Could the Medici’s famed aesthete

produce as excellent and sweet

as this famous derriere.

Did I say derriere?

Derriere too dainty.

Buttocks much too bawdy.

Cheeks so childishly petite.

Buns, impudently funny.

Rear end smacking of collision.

Ah, misnomered beauty.

Long-suffering

butt of jokes,

object of derision.

Pomegranate and apple

hath not such tempting

allure to me

as your hypnotic

anatomy.

Then

am I victim

of your spell,

bound since mine eyes

did first espy

that paradise of symmetry.

And like Pygmalion transfixed,

who sincere believed

desire could unfix

that alabaster chastity,

grieved the enchantment

of those small cruel hips—

those hard twin bones—

that house such enormous

happiness.

Trieste—Ciao to Italy

for Natale Mancari

Maybe we should’ve fallen in love.

Or pretended to be.

What was there to lose

except a few hours of sleep.

You needed me.

But that wasn’t reason enough.

And love is no charity,

no tin cup and yellow pencils.

What did we expect?

Trieste was full of disappointments—

a town that got lucky and had the sea.

And how could I explain in raggedy Italian

I still liked you.

Maybe when your train gets into Milano

and mine to Dubrovnik, we’ll perhaps regret

what didn’t happen. Maybe.

But any town with a name

this sad deserves nothing

but a stony memory.

Peaches—Six in a Tin Bowl, Sarajevo

If peaches had arms

surely they would hold one another

in their peach sleep.

And if peaches had feet

it is sure they would

nudge one another

with their soft peachy feet.

And if peaches could

they would sleep

with their dimpled head

on the other’s

each to each.

Like you and me.

And sleep and sleep.

Hydra Night—House on Fire

When houses burn here

you just watch.

There is nothing

but the sea

for irony.

Cinders wild as flies.

Rooster crowing day too early.

Night illumined. Moonless sky.

I worked with others

dragging furniture outdoors—

books, tables, lamps—

to save what could be saved.

Water drizzled from a skinny hose.

Buckets passed from

hand to hand to hand.

Somebody cursed in Greek.

A neighbor gave me her sweater,

asked if I was cold.

First the grape arbor came down.

And then the windows spoke.

We watched until the roof

sighed twice, then died.

Then one by one went home

to dream of fire.

Hydra Coming Down in Rain

I’m not certain

but I imagine even

mountains melt.

In Hydra

they come down

in rain

and down

on cobbled

steps

inside your shoes

unless your boots

are rubber

red.

Bleed

from lemon trees,

whitewashed walls,

wooden shutters,

gravel,

bougainvillea,

clay tile roof,

pomegranate,

copper gutter,

slippery flagstones,

fresh donkey shit,

and jasmine flowers.

Down and down

until the mountain

meets the port

and spills

into

the sea.

Fishing Calamari by Moon

for A. Stavrou

At the bullfights as a child

I always cheered for the bull,

that underdog of underdogs,

destined to lose, and I tell you

this, Andoni, so you’ll understand,

though we are miles from bullrings.

The Greek moon a lovely thing

to look at above our boat.

We are an international crew tonight.

Greek sea, African Queen, you, me.

But I am sad. Probably the only

foolish fisherman to cry

because we’ve caught a calamari.

You didn’t tell me how

their skins turn black

as sorrow. How they suck the air

in dying, a single terrifying cry

terrible as tin.

You will cook it in oil.

You will slice it and serve it

for our lunch tomorrow.

Endaxi—okay.

But tonight my heart

goes out to the survivors,

to the ones who get away.

To all underdogs everywhere,

bravo, Andoni. Olé.

Moon in Hydra

Women fled.

Tired of the myth

they had to live.

They no longer wait

for their Theseus

to rescue, then

abandon them.

Instead,

they take

the first boat out

to Athens.

Live alone.

No longer Hydra women

bound to stone.

Smoke rises

from the Athens shore,

and some say

it’s the fumes of autos,

motor scooters,

factory pollution.

But I think

it’s an ancient rage.

Women who grew tired

beneath the weight of years

that would not buckle,

break nor bend.

One Last Poem for Richard

December 24th and we’re through again.

This time for good I know because I didn’t

throw you out—and anyway we waved.

No shoes. No angry doors.

We folded clothes and went

our separate ways.

You left behind that flannel shirt

of yours I liked but remembered to take

your toothbrush. Where are you tonight?

Richard, it’s Christmas Eve again

and old ghosts come back home.

I’m sitting by the Christmas tree

wondering where did we go wrong.

Okay, we didn’t work, and all

memories to tell the truth aren’t good.

But sometimes there were good times.

Love was good. I loved your crooked sleep

beside me and never dreamed afraid.

There should be stars for great wars

like ours. There ought to be awards

and plenty of champagne for the survivors.

After all the years of degradations,

the several holidays of failure,

Have You Seen Marie?

Have You Seen Marie? Woman Hollering Creek: And Other Stories

Woman Hollering Creek: And Other Stories The House on Mango Street

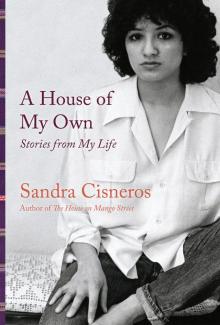

The House on Mango Street A House of My Own: Stories From My Life

A House of My Own: Stories From My Life Loose Woman

Loose Woman Caramelo

Caramelo Martita, I Remember You/Martita, te recuerdo

Martita, I Remember You/Martita, te recuerdo A House of My Own

A House of My Own My Wicked Wicked Ways

My Wicked Wicked Ways