- Home

- Sandra Cisneros

Loose Woman Page 5

Loose Woman Read online

Page 5

inside the triangle of that prayer.

Rose, tangerine, turquoise, jade,

Ave Maria blue. Sweet as an apricot,

soft as the silk fringe of my best shawl.

Mexican cutouts. Christmas faroles.

Bright as parasols, carnival, confetti.

You laughed, remember?

But that night.

Embroidered flowers, embroidered birds.

V

In the clatter of your departures,

I write poems.

Poems

the wind flutters.

Papel de China.

Paper flowers, paper wings.

A Man in My Bed Like Cracker Crumbs

I’ve stripped the bed.

Shaken the sheets and slumped

those fat pillows like tired tongues

out the window for air and sun

to get to. I’ve let

the mattress lounge in

its blue-striped dressing gown.

I’ve punched and fluffed.

All morning. I’ve billowed and snapped.

Said my prayers to la Virgen de la Soledad

and now I can sit down

to my typewriter and cup

because she’s answered me.

Coffee’s good.

Dust motes somersault and spin.

House clean.

I’m alone again.

Amen.

Bienvenido Poem for Sophie

This morning that would’ve meant

a field of crumpled snow if we

were in Vermont, brought only

a crumpled sky to Texas,

and you and Alba for breakfast

tacos at Torres Taco Haven

where you admired my table

next to the jukebox and

said, Good place to write.

You promised we could come back

and have tacos together and sit

here with coffee and our writer’s

notebooks whenever we want.

And nobody would have to talk

if we didn’t want to. Next time

you come by my house, I want

to take you up to the roof.

At sunset the grackles

make a wonderful racket.

You can come whenever you want.

And nobody will have to talk

if we don’t want to.

Arturito the Amazing Baby Olmec Who Is Mine by Way of Water

Arturito, when you were born

the hospital gasped when

they fished you from your fist of sleep,

a rude welcome you didn’t like a bit,

and I don’t blame you. The world’s a mess.

You inherited the family sleepiness and overslept.

And in that sea the days were nacre.

When you arrived on Mexican time,

you were a wonder, a splendor, a plunder,

more royal than any Olmec

and as mysterious and grand.

And everyone said “¡Ay!”

or “Oh!” depending on their native tongue.

So, here you are, godchild,

a marvel that could compete with any ancient god

asleep beneath the Campeche corn. A ti te tocó

the aunt who dislikes kids and Catholics,

your godmother. Don’t cry!

What do amazing godmothers do?

They give amazing gifts. Mine to you—

three wishes.

First, I wish you noble like Zapata,

because a man is one who guards

those weaker than himself.

Second, I wish you a Gandhi wisdom,

he knew power is not the fist,

he knew the power of the powerless.

Third, I wish you Mother Teresa generous.

Because the way of wealth is giving

yourself away to others.

Zapata, Gandhi, Mother Teresa.

Great plans! Grand joy! Amazingness!

For you, my godchild, nothing less.

These are my wishes, Arturo Olmec,

Arturito amazing boy.

Escribí este poema para mi ahijado, Arturo Javier Cisneros Zamora, el 8 de febrero, 1993, en San Antonio de Bexar, Tejas.

Jumping off Roofs

Bet your feet burned

when you landed.

That’s for sure.

Only child playing with your only self.

First the chicken shed

in the corrugated Laredo heat.

Then the roof of the big

house when mama and the aunts

were all asleep.

And years later,

off a plane on some fool dare

you couldn’t back out of.

So the story goes.

How your heart opened like silk.

The crooked spin of horizon.

That awful slant of sky.

And finally, the ripcord

and the yank

of life to bring you

back to earth.

Broke an ankle. Bone

split into a thousand colors.

Swell story to tell and tell again

at a San Antonio ice house.

But what I want to know is this.

In that dizzy moment

did your peepee dangle

like a ripcord,

or is it true all men

have hard-ons

when they fall to earth?

And if so,

what is the good

of being close to heaven

if our souls have business with the angels

but our peepees

so much to do with earth.

Why I Didn’t

Of course.

I was going to, you know.

Or maybe you didn’t.

Already my mouth gone soft

when you kissed me good night

and let me go.

But instead of love

there was only an old sleeping bag

you tossed at me and three

flea bites on my belly

the next morning.

You didn’t know that,

did you?

I didn’t think so.

Nor your name I stole

and took with me

all the way from San Antonio

to Puerto Escondido.

And today when I waited

for your pickup to appear,

I’ll be right back, and left me there

on your porch full of suitcases and

crates and saws and cedar,

I went into your room

and lay down on your bed

just to see if it’d suit me.

The sheets were cool

and a fine talc of dust lay everywhere

the way some men who live alone

are used to living.

Oh I’m scared all right.

Haven’t you noticed, I’m

only shy when I like a man.

And to tell the truth

I’m not sure love is worth

the risk of losing friendship.

It would’ve been easy.

I could’ve claimed

I was afraid of the dark.

I am, you know. Afraid I mean.

But there was that plane

to catch the next morning.

And you had to go to work.

Besides, I was sleepy.

And love, that fish too old to get away,

will be there the next morning. And if not,

there are other mornings, other fish.

Las Girlfriends

Tip the barmaid in tight jeans.

She’s my friend.

Been to hell and back again.

I’ve been there too.

Girlfriend, I believe in Gandhi.

But some nights nothing says it

quite precise like a Lone Star

cracked on so

meone’s head.

Last week in this same bar,

kicked a cowboy in the butt

who made a grab for Terry’s ass.

How do I explain, it was all

of Texas I was kicking,

and all our asses on the line.

At Tacoland, Cat flamencoing crazy

circles round the pool

player with the furry tongue.

A warpath of sorts for every

wrong ever wronged us.

And Terry here has her own history.

A bar down the street she can’t

go in, and one downtown. Me,

a French café in Austin

where they don’t say—entrez-vous.

Little Rose of San Antone

is the queen bee of kick-nalga.

When you go out with her,

don’t wear your good clothes.

But the best story is la Bárbara

who runs for the biggest kitchen knife

in the house every bad-ass domestic quarrel.

Points it towards her own heart

like some Aztec priestess gone loca.

¡ME MATO!

I tell you, nights like these,

something bubbles from

the tips of our pointy boots

to the top of our coyote yowl.

Ya’ll wicked mean, a voice at the bar

claims. Naw, not mean. Shit!

Been to hell and back again.

Girl, me too.

Champagne Poem for La Josie

for Josie Garza

The first glass will make you laugh.

The second will have you making others laugh.

The third is for singing operettas.

The fourth to give you wings.

The fifth will have you forget

the things you chose to remember

and remember things you chose to forget.

The sixth is for courage when dialing Him.

The seventh to bring down cuss and concupiscence.

Congratulations. The eighth will drive you to bed or brawl.

Or to brawl in bed. Same difference.

Still Life with Potatoes, Pearls, Raw Meat, Rhinestones, Lard, and Horse Hooves

for Franco Mondini

In Spanish it’s naturaleza muerta and not life at all.

But certainly not natural. What’s natural?

You and me. I’ll buy you a drink.

To a woman who doesn’t act like a woman.

To a man who doesn’t act like a man.

Death is natural, at least in Spanish, I think.

Life? I’m not so sure.

Consider The Contéssa, who in her time was lovely

and now sports a wart the size of this diamond.

So, ragazzo, you’re Venice.

To you. To Venice.

Not the one of Casanova.

The other one of cheap pensiones by the railway station.

I recommend a narrow bed stained with semen, pee, and sorrow facing the wall.

Stain and decay are romantic.

You’re positively Pasolini.

Likely to dangle and fandango yourself to death.

If we let you. I won’t let you!

Not to be outdone I’m Piazzolla.

I’ll tango for you in a lace G-string

stained with my first-day flow

and one sloppy tit leaping like a Niagara from my dress.

Did you say duress or dress?

Let’s sing a Puccini duet—I like La Traviesa.

I’ll be your trained monkey.

I’ll be sequin and bangle.

I’ll be Mae, Joan, Bette, Marlene for you—

I’ll be anything you ask. But ask me something glamorous.

Only make me laugh.

Another?

What I want to say, querido, is

hunger is not romantic to the hungry.

What I want to say is

fear is not so thrilling if you’re the one afraid.

What I want to say is

poverty’s not quaint when it’s your house you can’t escape from.

Decay’s not beautiful to the decayed.

What’s beauty?

Lipstick on a penis.

A kiss on a running sore.

A reptile stiletto that could puncture a heart.

A brick through the windshield that means I love you.

A hurt that bangs on the door.

Look, I hate to break this to you, but this isn’t Venice or Buenos Aires.

This is San Antonio.

That mirror isn’t a yard sale.

It’s a fire. And these are remnants

of what could be carried out and saved.

The pearls? I bought them at the Winn’s.

My mink? Genuine acrylic.

Thank God this isn’t Berlin.

Another drink?

Bartender, another bottle, but—

¡Ay caray and oh dear!—

The pretty blond boy is no longer serving us.

To the death camps! To the death camps!

How rude! How vulgar!

Drink up, honey. I’ve got money.

Doesn’t he know who we are?

Que vivan los de abajo de los de abajo,

los de rienda suelta, the witches, the women,

the dangerous, the queer.

Que vivan las perras.

“Que me sirvan otro trago …”

I know a bar where they’ll buy us drinks

if I wear my skirt on my head and you come in wearing nothing

but my black brassiere.

Vino Tinto

Dark wine reminds me of you.

The burgundies and cabernets.

The tang and thrum and hiss

that spiral like Egyptian silk,

blood bit from a lip, black

smoke from a cigarette.

Nights that swell like cork.

This night. A thousand.

Under a single lamplight.

In public or alone.

Very late or very early.

When I write my poems.

Something of you still taut

still tugs still pulls,

a rope that trembled

hummed between us.

Hummed, love, didn’t it.

Love, how it hummed.

Loose Woman

They say I’m a beast.

And feast on it. When all along

I thought that’s what a woman was.

They say I’m a bitch.

Or witch. I’ve claimed

the same and never winced.

They say I’m a macha, hell on wheels,

viva-la-vulva, fire and brimstone,

man-hating, devastating,

boogey-woman lesbian.

Not necessarily,

but I like the compliment.

The mob arrives with stones and sticks

to maim and lame and do me in.

All the same, when I open my mouth,

they wobble like gin.

Diamonds and pearls

tumble from my tongue.

Or toads and serpents.

Depending on the mood I’m in.

I like the itch I provoke.

The rustle of rumor

like crinoline.

I am the woman of myth and bullshit.

(True. I authored some of it.)

I built my little house of ill repute.

Brick by brick. Labored,

loved and masoned it.

I live like so.

Heart as sail, ballast, rudder, bow.

Rowdy. Indulgent to excess.

My sin and success—

I think of me to gluttony.

By all accounts I am

a danger to society.

I’m Pancha Villa.

I break laws,

upset the natural order,

anguish the Pope and make fathers cry.

&n

bsp; I am beyond the jaw of law.

I’m la desperada, most-wanted public enemy.

My happy picture grinning from the wall.

I strike terror among the men.

I can’t be bothered what they think.

¡Que se vayan a la ching chang chong!

For this, the cross, the Calvary.

In other words, I’m anarchy.

I’m an aim-well,

shoot-sharp,

sharp-tongued,

sharp-thinking,

fast-speaking,

foot-loose,

loose-tongued,

let-loose,

woman-on-the-loose

loose woman.

Beware, honey.

I’m Bitch. Beast. Macha.

¡Wáchale!

Ping! Ping! Ping!

I break things.

Sandra Cisneros was born in Chicago in 1954. Internationally acclaimed for her poetry and fiction, she has been the recipient of numerous awards, including the Lannan Literary Award and the American Book Award, and of fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts and the MacArthur Foundation. Cisneros is the author of two novels, The House on Mango Street and Caramelo; a collection of short stories, Woman Hollering Creek; two books of poetry, My Wicked Wicked Ways and Loose Woman; and a children’s book, Hairs/Pelitos. She is the founder of the Macondo Foundation, an association of writers united to serve underserved communities (www.macondofoundation.org), and is Writer in Residence at Our Lady of the Lake University, San Antonio. She lives in San Antonio, Texas. Find her online at www.sandracisneros.com.

Also by Sandra Cisneros

The House on Mango Street (English)

La casa en Mango Street (Spanish)

Woman Hollering Creek and Other Stories (English)

El Arroyo de la Llorona (Spanish)

My Wicked Wicked Ways (poetry)

Loose Woman (poetry)

Hairs/Pelitos (for young readers)

Caramelo (English)

Caramelo (Spanish)

Have You Seen Marie?

Have You Seen Marie? Woman Hollering Creek: And Other Stories

Woman Hollering Creek: And Other Stories The House on Mango Street

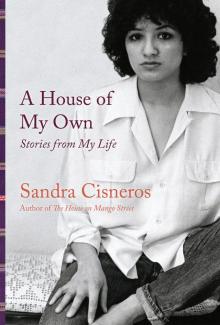

The House on Mango Street A House of My Own: Stories From My Life

A House of My Own: Stories From My Life Loose Woman

Loose Woman Caramelo

Caramelo Martita, I Remember You/Martita, te recuerdo

Martita, I Remember You/Martita, te recuerdo A House of My Own

A House of My Own My Wicked Wicked Ways

My Wicked Wicked Ways