- Home

- Sandra Cisneros

A House of My Own Page 6

A House of My Own Read online

Page 6

Nowadays, because I live in Texas, I prefer the huipiles from tierra caliente, the hot lands, especially from Oaxaca. They’re the ones I most often reach for to go to work—to write, that is. The fancy ones I save for being the Author.

For work, on the days I go barefoot, when I sometimes forget to comb my hair, when I’m anxious to forget my body and need to be comfortable, without any underclothes binding or biting me, I like my everyday huipiles de manta, of sackcloth. The ones I can stain with coffee or a taco and I won’t grieve. The ones I can throw in the wash. My Mexican muumuus, my prison clothes, my housedresses.

My spiritual mother and maestra is la Señora María Luísa Camacho de López, a walking Smithsonian of stories and information regarding Mexican folklore. I learned what I know about textiles thanks to this hija de rebocero, shawl-maker’s daughter. Several of my prize pieces once belonged to her.*2

I haven’t inherited any textiles from any of my real antepasados, ancestors, I’m sorry to say.*3 I didn’t know them. All I’ve got is a framed baby’s pillowcase my great-grandmother Victoria Rizo de Anguiano embroidered for the infant Elvira Cordero, my mother. A donkey in silk threads and the initials “E.C.”

Credit 6.2

La Señora María Luísa Camacho de López

In my antique Mexican trunks, I preserve my collection of huipiles. I like to think the huipiles I own were made by women like my grandmothers, and were, in a sense, their library.

Maybe the women of my family wove on a backstrap loom hooked to a tree in the courtyard, or maybe they embroidered in the shade, after their housework was done. And instead of writing books, which they could not do, they created a universe with designs as intricate and complex as any novel. These things I think because I can’t imagine my literary antecedents writing any other way than with needle and thread, weft and warp.

I consider the irony of being able to purchase huipiles made by women who go barefoot. Now only the most privileged North American ladies can afford to buy the museum-quality huipiles. Ladies like me.

In San Antonio there’s a group of women called “las Huipilistas,” a new class of Latinas. They’re professors, lawyers, artists, and activists who can afford to snatch up with the fervor of game hunters the very fine huipiles that cross our paths, because they’re getting harder and harder to find. In a time when 75 percent of the manufacturing industry is owned by American corporations operating in Mexico, when indigenous communities can no longer afford to stay in their villages and are forced to migrate north, the craft of these textiles may be lost altogether, and this clothing gone forever.

It’s been more than two decades since Norma and I made that trip south to San Cristóbal. Norma, the retired university professor, who favors T-shirts and sweats, hot-pink streaks in her hair, and high-top tennis shoes, recently asked me this favor: “Hey, Sandra, next time you go to Mexico, see if you can’t find me a huipil. I’d like to hang one on my wall.” That’s how it begins, I think.

Each time I wear a huipil, I’m saying, “Look, I know I can afford Neiman Marcus, but I’d rather wear an indigenous designer from Mexico, something no one else in the room will be wearing.”

I wear this textile as a way for me to resist the mexiphobia going on under the guise of Homeland Security. To acknowledge I’m not in agreement with the border vigilantes. To say I’m of las Americas, both North and South. This cloth is the flag of who I am.

* * *

*1 And here my comadre writer Liliana Valenzuela, who translates my books into Spanish, interrupts me for one moment: “Some women in Mexico City (and maybe other parts of the república) have been wearing indigenous clothing, perhaps since Frida Kahlo and other artists after the Mexican Revolution, and more recently during the ’60s, ’70s, ’80s, and probably even now, mostly in universities. I remember when wearing huipiles and blusas de manta and huaraches de cuero y suela de llanta was de rigueur when I was an anthro student in Mexico City in 1980. We were a bit unusual, but by no means the only ones doing so. We perhaps would not mix and match the items with modern or items from other countries like you do, but in all fairness, some anti-imperialist mexicanas y mexicanos have been wearing these clothes for some time, mostly with jeans. I guess it was a statement of going against the grain of current commercial fashion, solidarity with indigenous communities, coolness factor, and who knows what else.”

*2 They recently were donated to the National Museum of Mexican Art.

*3 Since writing this, I now have in my possession a shawl—rebozo de bolita—I found among my mother’s things when she died. My aunt Margaret recently gave me a Virgen de Guadalupe souvenir scarf from the 1940s that once belonged to Felipa Anguiano, my grandmother. I added these textiles to my installation “A Room of Her Own,” an altar for my mother exhibited at the National Museum of Mexican Art, Chicago; the National Hispanic Cultural Center, Albuquerque (a photo of this installation is on this page); the Smithsonian American History Museum, Washington, D.C.; and the Museum of Latin American Art, Long Beach, California.

Vivan los Muertos

Elle magazine approached me to write a travel feature for their October 1991 issue, but since I’d just come home from being on the road, I offered to write about an earlier trip I’d taken in 1985 to Mexico, in the wake of the worst earthquake of the century. I wish I’d written about what I’d seen in Mexico City that autumn when the destruction created a citywide Day of the Dead installation on every block. Or of the guerrilla artists who camped out in Tepito, one of the city’s poorest and most vice-ridden neighborhoods, and taught art under plastic tents set up in the streets. Or about the San Antonio Abad seamstresses who rose up from the wreckage of their sweatshops and created a labor union after witnessing bosses hauling out machinery from the factories instead of searching for coworkers. Or of the two seamstresses invited to Austin for a fund-raiser to benefit their union. They stayed with me at the Dobie Paisano Ranch during my residency in the fall of 1995. On the night of their event, flash floods locked us in, but not even roiling waters could stop these determined women. Austin buddies drove up to the opposite shore of the creek and tossed a rope. I watched as the two mexicanas waded safely across the raging stream as bravely as St. Christopher and the infant Jesus. The fund-raiser turned out to be a great success, raising a lot of money for the garment workers’ cause. But by the time I gathered my thoughts for the following piece, the quake (at least in the U.S.) was yesterday’s news.

My family doesn’t celebrate Day of the Dead. Nobody in our neighborhood sets up an ofrenda altar in memory of deceased ancestors.* I was north-of-the-border born and bred, an American Mexican from “Chicano, Illinois,” street tough and city smart, wise to the ways of trick or treat. I looked at the dead as American kids do, through the filter of too many Boris Karloff movies and Halloween.

I wish I’d grown up closer to the border like my friend María Limón of El Paso. There, as in Mexico, Day of the Dead can be an occasion for whole families to trek out to the camposanto, the holy ground, with brooms, buckets, and lunch basket, a day to feast with the ancestors who once a year return del mas allá, from the beyond, November lst for the angelitos, the dead children, November 2nd for deceased adults. Gravesites are weeded, tombstones washed, fresh flowers arranged, and an offering of favorite food set out for the deceased—an on-the-spot picnic for the dead and the living.

I once asked my Mexican father, “Didn’t you ever have an altar for Day of the Dead when you were little?”

“I think your abuela lit candles on her dresser and prayed,” he said.

“But no ofrenda in the living room, no dishes of mole, and xempoaxóchitl, marigold flowers, no midnight vigils in the cemetery, no shot glasses of tequila set out for the departed, no sugar skulls or loaves of pan de muerto, or calavera poems, or copal incense, or paper-cutout decorations, or framed photos of family members, or anything?”

My father’s mother, Trinidad del Moral

“No, no, no, no, no,” my father sai

d. “We’re from the city. That custom belongs to the Indians.” In other words, my father’s Mexico City family was too middle class, too “Spanish” for that pagan phenomenon whose roots go back to a pre-Columbian America.

The year María Limón and I went to Mexico in search of Day of the Dead I was thirty. As the naive American children of immigrants, we were filled with nostalgia for an imaginary country—one that exists only in images borrowed from art galleries and old Mexican movies. We wanted to know Death with her Mexican nicknames: La Flaca, La Calaca, La Catrina, La Huesuda, La Pelona, La Apestosa, La Llorona. Skinny, Skeleton, She-Dandy, Boney, Baldy, Stinky, Weeping One.

That same year, Death herself swept through the streets of Mexico City. The earthquake of 1985 claimed at least ten thousand lives. We went to investigate personally who needed our financial assistance the most, since we didn’t trust handing our relief funds to the government agencies. On any given block in the capital spontaneous curbside ofrendas appeared before the rubble of a building—votive candles and marigolds scattered next to a heap of family photographs, a child’s toy, a dusty stray shoe.

Our ganas de conocer, our longing to know, eventually led us to the state of Michoacán, west of Mexico City. It was a short trip to Morelia, the state capital, a quick bus ride to Pátzcuaro, and then a ferry across the lake to the island village Janitzio, famous for its fishermen who still fish with those beautiful butterfly nets and for its Day of the Dead festivities.

Like the returning deceased, we were returning from the beyond too, from el más allá. From el norte, where the tradition of Day of the Dead would be all but forgotten except for a generation of artists who have reintroduced it to the community in an attempt to reclaim a part of our indigenous past. We were making our way south the way our ancestors had made their way north.

“¿De dónde vienen?” the Pátzcuaro vendors asked us, our clothes and accents giving us away. “From Chicago, El Paso, Austin, San Antonio.” Ah, pochas, they thought—that awful word meaning north-of-the-border Mexicans.

We spent the day at the Pátzcuaro market watching the town prepare for the night’s celebration: women carrying bundles of marigolds, red cockscomb, and airy bunches of Mexican baby’s breath called nubes, clouds; market stalls throbbing with oranges displayed in radiant pyramids, dizzying palettes of spices, towers of chocolate for mole, and huge stalks of sugarcane.

In the main plaza under the arcades, the candy lady let us take pictures if we’d buy something. ¡Muy bonito! Her candy pretty with pastel icing, glitter, and foil. Marzipan hearts decorated with roses, sugar ladies and sugar dogs, sugar ducks and sugar angels, sugar corpses in their sugar coffins, all arranged neatly on freshly ironed embroidered cloth. I picked a sugar skull and had my name added with blue icing, a personalized service at no extra charge.

The toy vendor sold the Mexican version of the chattering teeth—a chattering skull, pull-string skeleton puppets, skeleton miniatures with Death doing everything from driving a taxicab to playing in a mariachi band. Shelves of the traditional Day of the Dead bread were on display as well, round loaves with bone designs on top, or corpses with their hands folded on their breasts. Everywhere the living busied themselves with this business of welcoming the recent and the long-ago dead.

That night, as we rode the ferry across Lake Pátzcuaro and the fog began to rise from the lake, the village of Janitzio spiraled from the water, lit as bright as a birthday cake. All the shops open, strings of lights decorating everything. Vendors welcomed our arrival hawking fish cakes from big baskets. Doorways were framed with arcs of marigolds.

The doors were left open to allow passersby to peer in and admire the altars. In one house with heavy wooden doors, an old woman sat alone in a room aflame with a thousand candles illuminating a sea of photographs, the dead in her life outnumbering the living.

We wound our way past a huge public altar in the main plaza, dedicated to the victims of the Mexico City disaster, toward the church graveyard. The camposanto was just a bald square of dust, a walled dirt yard lumpy with haphazard headstones, nothing at all like the cemeteries we know in the United States where everything is neat order and disciplined grass.

The villagers busied themselves finding their relatives. “Are you there? How are you?” Candles were set up on the grave slab. A symmetry of flowers. A bowl with clean, starched linen and Day of the Dead bread. Some yellow and orange squash for color. Dishes and candleholders all saved for this once-a-year occasion.

María Limón and I had brought our own ofrenda. We sat down on a tombstone no one had remembered and set out our offering to her father and to my grandfather. I had brought a cigar and a Kraft caramel for my abuelito, and María had her father’s passport with his last photo. Would the little dead one sleeping here mind if we borrowed his grave? We’d come from so far away. A villager at the next tombstone nudged her family and pointed to us with her chin, but no one said anything. Compared to everyone else busy arranging flowers and food, our portable ofrenda looked pretty sad. “It’s the thought that counts,” I said to María.

“And do you stay here with the food all night?” we asked our neighbors.

“Oh, no, we just keep a vigil for a while and then take the food home after the spirits have visited and savored it all.”

But how late, I don’t know. We were so cold sitting on that slab of rock, as if Death herself were piercing us, that we left before the vigil was over.

Because we weren’t able to find a room in Pátzcuaro, we had to flag down a bus to take us to Uruapan, an hour away. We found two seats next to a window that wouldn’t close. We stuffed the night dampness out with wadded newspaper and tried to sleep. The night wind of Michoacán smelled of sweet grass.

Was it right, do you think, to do what we’d done and place our little makeshift altar there? We’d meant well. Two pochas dressed in blue jeans and berets. Maybe we hadn’t seen the spirits. Maybe the spirits could be seen only by the villagers. I wasn’t sure. All the ride back I’m thinking. That fine split between my Mexican self and my ’Merican self, those two halves that don’t fit.

“María, I’m afraid of ghosts, aren’t you? Sometimes I get terrible nightmares.”

“Those are just bad spirits trying to mess with you when you’re asleep,” María said. “Don’t you know any good spirits?”

“Spirits?”

“Like someone you were close to when they were alive; your grandfather maybe.”

“My abuelito?”

“He’s a spirit. Next time you have a bad dream call your abuelito. Whenever you’re afraid, just call him. He’ll protect you.”

I hadn’t thought about my grandfather being someone whose strength I could summon the way I called my family when I needed a loan. The idea of a ghost being familia, someone who loved you and would never hurt you, was new to me.

María Limón fell asleep before I could ask her any more questions. I watched the landscape rise and fall, thick leafy silhouettes across the green, green land and sky a deep thing, the moon following and following us, whole and round and perfect.

* * *

* At the time I wrote this I was spiritually innocent. I’ve learned a lot since and install ofrendas regularly as a ritual of memory and respect, and for personal transformation.

Straw into Gold

In the spring of 1987, I was living in Austin, Texas, in a garage apartment too small even for two people furiously in love. To add further sorrow to the situation, I was unemployed most of the eight months there.

This lecture was written before hope ran out. Dr. Harriett Romo, then a professor at the University of Texas, invited me to speak to her class. This was before Austin gave me the boot to Chico, California, and my first university job.

I was still optimistic when I wrote this and had the ambitious idea to create a lecture that included slides thanks to the assistance of my then paramour, a photographer.

If some of the sentences sound overly dramatic and smug, it’s becau

se they were undercut by a funny visual, or because I was genuinely amazed at my life at the time. I repeated the lecture many times after until, in one of my many moves across the country, the slide carousel was stolen from a San Antonio storage unit. (Luckily, I have most of the original photos.) In retrospect, it’s an ironically upbeat portrait of my life given that by the end of 1987 I’d blaze into a meteoric depression I’d later dub Hell’s Basement.

When I was living in an artists’ colony in the south of France, some fellow Latin Americans who taught at the university in Aix-en-Provence invited me to share a home-cooked meal with them. I had been living abroad almost a year then on my writing grant, subsisting mainly on French bread and lentils so that my money would last longer. So when the invitation to dinner arrived, I accepted without hesitation. Especially because they promised Mexican food.

Self-portrait on my front porch, Vence, 1983

What I didn’t realize when they made this invitation was that I was supposed to be involved in preparing the meal. I guess they assumed I knew how to cook Mexican food because I’m Mexican. They wanted specifically tortillas, though I’d never made a tortilla in my life.

It’s true I’d witnessed my mother rolling the little armies of dough into perfect circles, but my mother’s family is from Guanajuato—provincianos, country folk. They knew only how to make flour tortillas.*1 My father’s family, on the other hand, is chilango, from Mexico City. We ate corn tortillas, but we didn’t make them. Someone*2 was sent to the corner tortillería to buy them. I’d never seen anybody make corn tortillas. Ever.

Have You Seen Marie?

Have You Seen Marie? Woman Hollering Creek: And Other Stories

Woman Hollering Creek: And Other Stories The House on Mango Street

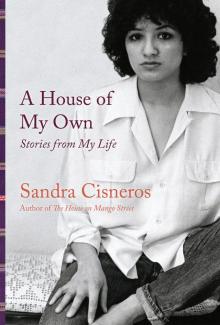

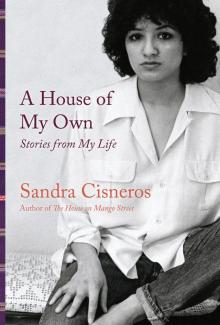

The House on Mango Street A House of My Own: Stories From My Life

A House of My Own: Stories From My Life Loose Woman

Loose Woman Caramelo

Caramelo Martita, I Remember You/Martita, te recuerdo

Martita, I Remember You/Martita, te recuerdo A House of My Own

A House of My Own My Wicked Wicked Ways

My Wicked Wicked Ways