- Home

- Sandra Cisneros

The House on Mango Street Page 7

The House on Mango Street Read online

Page 7

In the movies there is always one with red red lips who is beautiful and cruel. She is the one who drives the men crazy and laughs them all away. Her power is her own. She will not give it away.

I have begun my own quiet war. Simple. Sure. I am one who leaves the table like a man, without putting back the chair or picking up the plate.

A Smart Cookie

I could’ve been somebody, you know? my mother says and sighs. She has lived in this city her whole life. She can speak two languages. She can sing an opera. She knows how to fix a T.V. But she doesn’t know which subway train to take to get downtown. I hold her hand very tight while we wait for the right train to arrive.

She used to draw when she had time. Now she draws with a needle and thread, little knotted rosebuds, tulips made of silk thread. Someday she would like to go to the ballet. Someday she would like to see a play. She borrows opera records from the public library and sings with velvety lungs powerful as morning glories.

Today while cooking oatmeal she is Madame Butterfly until she sighs and points the wooden spoon at me. I could’ve been somebody, you know? Esperanza, you go to school. Study hard. That Madame Butterfly was a fool. She stirs the oatmeal. Look at my comadres. She means Izaura whose husband left and Yolanda whose husband is dead. Got to take care all your own, she says shaking her head.

Then out of nowhere:

Shame is a bad thing, you know. It keeps you down. You want to know why I quit school? Because I didn’t have nice clothes. No clothes, but I had brains.

Yup, she says disgusted, stirring again. I was a smart cookie then.

What Sally Said

He never hits me hard. She said her mama rubs lard on all the places where it hurts. Then at school she’d say she fell. That’s where all the blue places come from. That’s why her skin is always scarred.

But who believes her. A girl that big, a girl who comes in with her pretty face all beaten and black can’t be falling off the stairs. He never hits me hard.

But Sally doesn’t tell about that time he hit her with his hands just like a dog, she said, like if I was an animal. He thinks I’m going to run away like his sisters who made the family ashamed. Just because I’m a daughter, and then she doesn’t say.

Sally was going to get permission to stay with us a little and one Thursday she came finally with a sack full of clothes and a paper bag of sweetbread her mama sent. And would’ve stayed too except when the dark came her father, whose eyes were little from crying, knocked on the door and said please come back, this is the last time. And she said Daddy and went home.

Then we didn’t need to worry. Until one day Sally’s father catches her talking to a boy and the next day she doesn’t come to school. And the next. Until the way Sally tells it, he just went crazy, he just forgot he was her father between the buckle and the belt.

You’re not my daughter, you’re not my daughter. And then he broke into his hands.

The

Monkey

Garden

The monkey doesn’t live there anymore. The monkey moved—to Kentucky—and took his people with him. And I was glad because I couldn’t listen anymore to his wild screaming at night, the twangy yakkety-yak of the people who owned him. The green metal cage, the porcelain table top, the family that spoke like guitars. Monkey, family, table. All gone.

And it was then we took over the garden we had been afraid to go into when the monkey screamed and showed its yellow teeth.

There were sunflowers big as flowers on Mars and thick cockscombs bleeding the deep red fringe of theater curtains. There were dizzy bees and bow-tied fruit flies turning somersaults and humming in the air. Sweet sweet peach trees. Thorn roses and thistle and pears. Weeds like so many squinty-eyed stars and brush that made your ankles itch and itch until you washed with soap and water. There were big green apples hard as knees. And everywhere the sleepy smell of rotting wood, damp earth and dusty hollyhocks thick and perfumy like the blue-blond hair of the dead.

Yellow spiders ran when we turned rocks over and pale worms blind and afraid of light rolled over in their sleep. Poke a stick in the sandy soil and a few blue-skinned beetles would appear, an avenue of ants, so many crusty lady bugs. This was a garden, a wonderful thing to look at in the spring. But bit by bit, after the monkey left, the garden began to take over itself. Flowers stopped obeying the little bricks that kept them from growing beyond their paths. Weeds mixed in. Dead cars appeared overnight like mushrooms. First one and then another and then a pale blue pickup with the front windshield missing. Before you knew it, the monkey garden became filled with sleepy cars.

Things had a way of disappearing in the garden, as if the garden itself ate them, or, as if with its old-man memory, it put them away and forgot them. Nenny found a dollar and a dead mouse between two rocks in the stone wall where the morning glories climbed, and once when we were playing hide-and-seek, Eddie Vargas laid his head beneath a hibiscus tree and fell asleep there like a Rip Van Winkle until somebody remembered he was in the game and went back to look for him.

This, I suppose, was the reason why we went there. Far away from where our mothers could find us. We and a few old dogs who lived inside the empty cars. We made a clubhouse once on the back of that old blue pickup. And besides, we liked to jump from the roof of one car to another and pretend they were giant mushrooms.

Somebody started the lie that the monkey garden had been there before anything. We liked to think the garden could hide things for a thousand years. There beneath the roots of soggy flowers were the bones of murdered pirates and dinosaurs, the eye of a unicorn turned to coal.

This is where I wanted to die and where I tried one day but not even the monkey garden would have me. It was the last day I would go there.

Who was it that said I was getting too old to play the games? Who was it I didn’t listen to? I only remember that when the others ran, I wanted to run too, up and down and through the monkey garden, fast as the boys, not like Sally who screamed if she got her stockings muddy.

I said, Sally, come on, but she wouldn’t. She stayed by the curb talking to Tito and his friends. Play with the kids if you want, she said, I’m staying here. She could be stuck-up like that if she wanted to, so I just left.

It was her own fault too. When I got back Sally was pretending to be mad … something about the boys having stolen her keys. Please give them back to me, she said punching the nearest one with a soft fist. They were laughing. She was too. It was a joke I didn’t get.

I wanted to go back with the other kids who were still jumping on cars, still chasing each other through the garden, but Sally had her own game.

One of the boys invented the rules. One of Tito’s friends said you can’t get the keys back unless you kiss us and Sally pretended to be mad at first but she said yes. It was that simple.

I don’t know why, but something inside me wanted to throw a stick. Something wanted to say no when I watched Sally going into the garden with Tito’s buddies all grinning. It was just a kiss, that’s all. A kiss for each one. So what, she said.

Only how come I felt angry inside. Like something wasn’t right. Sally went behind that old blue pickup to kiss the boys and get her keys back, and I ran up three flights of stairs to where Tito lived. His mother was ironing shirts. She was sprinkling water on them from an empty pop bottle and smoking a cigarette.

Your son and his friends stole Sally’s keys and now they won’t give them back unies she kisses them and right now they’re making her kiss them, I said all out of breath from the three flights of stairs.

Those kids, she said, not looking up from her ironing.

That’s all?

What do you want me to do, she said, call the cops? And kept on ironing.

I looked at her a long time, but couldn’t think of anything to say, and ran back down the three flights to the garden where Sally needed to be saved. I took three big sticks and a brick and figured this was enough.

But when I got there Sally sa

id go home. Those boys said leave us alone. I felt stupid with my brick. They all looked at me as if I was the one that was crazy and made me feel ashamed.

And then I don’t know why but I had to run away. I had to hide myself at the other end of the garden, in the jungle part, under a tree that wouldn’t mind if I lay down and cried a long time. I closed my eyes like tight stars so that I wouldn’t, but I did. My face felt hot. Everything inside hiccupped.

I read somewhere in India there are priests who can will their heart to stop beating. I wanted to will my blood to stop, my heart to quit its pumping. I wanted to be dead, to turn into the rain, my eyes melt into the ground like two black snails. I wished and wished. I closed my eyes and willed it, but when I got up my dress was green and I had a headache.

I looked at my feet in their white socks and ugly round shoes. They seemed far away. They didn’t seem to be my feet anymore. And the garden that had been such a good place to play didn’t seem mine either.

Red Clowns

Sally, you lied. It wasn’t what you said at all. What he did. Where he touched me. I didn’t want it, Sally. The way they said it, the way it’s supposed to be, all the storybooks and movies, why did you lie to me?

I was waiting by the red clowns. I was standing by the tilt-a-whirl where you said. And anyway I don’t like carnivals. I went to be with you because you laugh on the tilt-a-whirl, you throw your head back and laugh. I hold your change, wave, count how many times you go by. Those boys that look at you because you’re pretty. I like to be with you, Sally. You’re my friend. But that big boy, where did he take you? I waited such a long time. I waited by the red clowns, just like you said, but you never came, you never came for me.

Sally Sally a hundred times. Why didn’t you hear me when I called? Why didn’t you tell them to leave me alone? The one who grabbed me by the arm, he wouldn’t let me go. He said I love you, Spanish girl, I love you, and pressed his sour mouth to mine.

Sally, make him stop. I couldn’t make them go away. I couldn’t do anything but cry. I don’t remember. It was dark. I don’t remember. I don’t remember. Please don’t make me tell it all.

Why did you leave me all alone? I waited my whole life. You’re a liar. They all lied. All the books and magazines, everything that told it wrong. Only his dirty fingernails against my skin, only his sour smell again. The moon that watched. The tilt-a-whirl. The red clowns laughing their thick-tongue laugh.

Then the colors began to whirl. Sky tipped. Their high black gym shoes ran. Sally, you lied, you lied. He wouldn’t let me go. He said I love you, I love you, Spanish girl.

Linoleum Roses

Sally got married like we knew she would, young and not ready but married just the same. She met a marshmallow salesman at a school bazaar, and she married him in another state where it’s legal to get married before eighth grade. She has her husband and her house now, her pillowcases and her plates. She says she is in love, but I think she did it to escape.

Sally says she likes being married because now she gets to buy her own things when her husband gives her money. She is happy, except sometimes her husband gets angry and once he broke the door where his foot went through, though most days he is okay. Except he won’t let her talk on the telephone. And he doesn’t let her look out the window. And he doesn’t like her friends, so nobody gets to visit her unless he is working.

She sits at home because she is afraid to go outside without his permission. She looks at all the things they own: the towels and the toaster, the alarm clock and the drapes. She likes looking at the walls, at how neatly their corners meet, the linoleum roses on the floor, the ceiling smooth as wedding cake.

The

Three

Sisters

They came with the wind that blows in August, thin as a spider web and barely noticed. Three who did not seem to be related to anything but the moon. One with laughter like tin and one with eyes of a cat and one with hands like porcelain. The aunts, the three sisters, las comadres, they said.

The baby died. Lucy and Rachel’s sister. One night a dog cried, and the next day a yellow bird flew in through an open window. Before the week was over, the baby’s fever was worse. Then Jesus came and took the baby with him far away. That’s what their mother said.

Then the visitors came … in and out of the little house. It was hard to keep the floors clean. Anybody who had ever wondered what color the walls were came and came to look at that little thumb of a human in a box like candy.

I had never seen the dead before, not for real, not in somebody’s living room for people to kiss and bless themselves and light a candle for. Not in a house. It seemed strange.

They must’ve known, the sisters. They had the power and could sense what was what. They said, Come here, and gave me a stick of gum. They smelled like Kleenex or the inside of a satin handbag, and then I didn’t feel afraid.

What’s your name, the cat-eyed one asked.

Esperanza, I said.

Esperanza, the old blue-veined one repeated in a high thin voice. Esperanza … a good good name.

My knees hurt, the one with the funny laugh complained.

Tomorrow it will rain.

Yes, tomorrow, they said.

How do you know? I asked.

We know.

Look at her hands, cat-eyed said.

And they turned them over and over as if they were looking for something.

She’s special.

Yes, she’ll go very far.

Yes, yes, hmmm.

Make a wish. A wish?

Yes, make a wish. What do you want?

Anything? I said.

Well, why not?

I closed my eyes.

Did you wish already?

Yes, I said.

Well, that’s all there is to it. It’ll come true.

How do you know? I asked.

We know, we know.

Esperanza. The one with marble hands called me aside. Esperanza. She held my face with her blue-veined hands and looked and looked at me. A long silence. When you leave you must remember always to come back, she said.

What?

When you leave you must remember to come back for the others. A circle, understand? You will always be Esperanza. You will always be Mango Street. You can’t erase what you know. You can’t forget who you are.

Then I didn’t know what to say. It was as if she could read my mind, as if she knew what I had wished for, and I felt ashamed for having made such a selfish wish.

You must remember to come back. For the ones who cannot leave as easily as you. You will remember? She asked as if she was telling me. Yes, yes, I said a little confused.

Good, she said, rubbing my hands. Good. That’s all. You can go.

I got up to join Lucy and Rachel who were already outside waiting by the door, wondering what I was doing talking to three old ladies who smelled like cinnamon. I didn’t understand everything they had told me. I turned around. They smiled and waved in their smoky way.

Then I didn’t see them. Not once, or twice, or ever again.

Alicia & I

Talking

on

Edna’s Steps

I like Alicia because once she gave me a little leather purse with the word GUADALAJARA stitched on it, which is home for Alicia, and one day she will go back there. But today she is listening to my sadness because I don’t have a house.

You live right here, 4006 Mango, Alicia says and points to the house I am ashamed of.

No, this isn’t my house I say and shake my head as if shaking could undo the year I’ve lived here. I don’t belong. I don’t ever want to come from here. You have a home, Alicia, and one day you’ll go there, to a town you remember, but me I never had a house, not even a photograph … only one I dream of.

No, Alicia says. Like it or not you are Mango Street, and one day you’ll come back too.

Not me. Not until somebody makes it better.

Who’s going to do it? The mayor?

And the thought of the mayor coming to Mango Street makes me laugh out loud.

Who’s going to do it? Not the mayor.

A

House

of

My Own

Not a flat. Not an apartment in back. Not a man’s house. Not a daddy’s. A house all my own. With my porch and my pillow, my pretty purple petunias. My books and my stories. My two shoes waiting beside the bed. Nobody to shake a stick at. Nobody’s garbage to pick up after.

Only a house quiet as snow, a space for myself to go, clean as paper before the poem.

Mango

Says

Goodbye

Sometimes

I like to tell stories. I tell them inside my head. I tell them after the mailman says, Here’s your mail. Here’s your mail he said.

I make a story for my life, for each step my brown shoe takes. I say, “And so she trudged up the wooden stairs, her sad brown shoes taking her to the house she never liked.”

I like to tell stories. I am going to tell you a story about a girl who didn’t want to belong.

We didn’t always live on Mango Street. Before that we lived on Loomis on the third floor, and before that we lived on Keeler. Before Keeler it was Paulina, but what I remember most is Mango Street, sad red house, the house I belong but do not belong to.

I put it down on paper and then the ghost does not ache so much. I write it down and Mango says goodbye sometimes. She does not hold me with both arms. She sets me free.

One day I will pack my bags of books and paper. One day I will say goodbye to Mango. I am too strong for her to keep me here forever. One day I will go away.

Friends and neighbors will say, What happened to that Esperanza? Where did she go with all those books and paper? Why did she march so far away?

Have You Seen Marie?

Have You Seen Marie? Woman Hollering Creek: And Other Stories

Woman Hollering Creek: And Other Stories The House on Mango Street

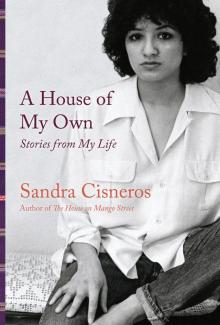

The House on Mango Street A House of My Own: Stories From My Life

A House of My Own: Stories From My Life Loose Woman

Loose Woman Caramelo

Caramelo Martita, I Remember You/Martita, te recuerdo

Martita, I Remember You/Martita, te recuerdo A House of My Own

A House of My Own My Wicked Wicked Ways

My Wicked Wicked Ways