- Home

- Sandra Cisneros

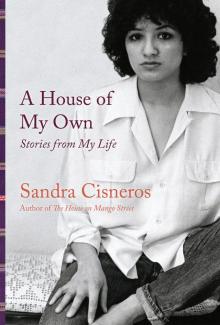

A House of My Own Page 10

A House of My Own Read online

Page 10

I want to believe that everyone falls in love with a book in much the same way one falls in love with a person, that one has an intimate, personal exchange, a mystical exchange, as spiritual and charged as the figure eight meaning infinity.

I remember the bus ride from Oaxaca City to San Cristóbal de las Casas, and how somewhere after Tuxtla Gutiérrez, in the dizzy road between that city and San Cristóbal, I finished Marguerite Duras’s The Lover.

And I recall an especially unforgettable rainy night in a London garret forfeiting dinner for Jeanette Winterson’s The Passion, as if it were an indulgence of expensive chocolate creams.

So I first read Mercè Rodoreda’s novel The Time of the Doves under the sun in a courtyard in Berkeley, California, on the hottest day of autumn, 1988, and only when I finished the book did I raise my head and realize I was sitting in the hydrangea blue of twilight.

I have borrowed, I have learned from this borrowing.

The following first appeared as an introduction to the Graywolf Press edition of Camellia Street, September 1993. It was written before Internet search engines were ubiquitous.

There are no camellias on Camellia Street. Maybe once, recent or long ago, but not when I was there last spring. “Las calles han sido siempre para mí motivo de inspiración…” Rodoreda wrote in a prologue to one of her novels, “The streets have always motivated me to write.” So it’s on the streets of Barcelona I go in search of her.

Of Rodoreda one French critic said, “One feels that this little working woman in Barcelona has spoken on behalf of all the hope, all the freedom, and all the courage in the world. And that she has just uttered forth one of the books of most universal relevance that love—let us finally say the word—could have written.” He was talking of The Time of the Doves, a novel introduced to me by a Texas parking lot attendant—“Don’t you know Mercè Rodoreda?” he asked. “García Márquez considers her one of the greatest writers of this century.” A recommendation by García Márquez and a parking lot attendant. They couldn’t both be wrong. I asked the attendant to scribble Rodoreda’s name on a check deposit slip, and a year later, I bought the book and read it cover to cover all in one afternoon. When I was finished, I felt as foolish as Balboa discovering the powerful Pacific.

Who is this writer, this “little working woman” who arrived too many years too late in my life, but just in time. What I know of Rodoreda I’ve gathered from introductions, prologues, blurbs, book jackets—bits and pieces from here and there that tell me facts, that tell me nothing. I know she was born on the 10th of October (1909 according to one source, 1908 according to another), an only daughter—like me—of overprotective parents, but unlike me, she is an only child. At twenty-five she publishes her first novel. At thirty, she receives a prestigious literary prize for her book Aloma. She is a prolific writer in the years before the Spanish Civil War, writing novels, publishing short stories in several important literary journals. Was she married? Did she have children? Did her husband want her to follow her life of letters or did he say, “Mercè, enough of that, come to bed already”? And when she went to bed, did she wish he wasn’t there so she could go to bed with a book? I don’t know for certain, but I wonder.

I know with the war she takes refuge for a time in Paris, and, later, Geneva. Some of her books—The Time of the Doves, for example—are finished in Geneva, where David Rosenthal, her English translator, says she eked out a survivor’s existence, but what exactly does he mean? Did she mop bathrooms and tug bed linens taut, type doctoral dissertations, wipe the milk moustache from the mouth of a small child, embroider blue stars on sheets and pillowcases? Or work in a bakery like Colometa, the protagonist of The Time of the Doves, her fingers tired from tying ribbons into bows all day? I can’t know.

For two decades when she lives exiled from her language, Rodoreda does not write. At least, she does not publish. I know she has said that during this time she couldn’t bear the thought of literature, that literature made her feel like vomiting, that she was never as lucid as during this period when she was starving. I imagine myself the months I lived without English in Sarajevo, or the year I lived without Spanish in Northern California—both times not writing because I could not brave repeating my life on paper. I slept for hours hoping the days would roll by, my life dried and hollow like a seedpod. What would a writer do not writing for a year? For twenty?

She is in her early fifties when she begins to write again, her masterpiece—La plaça del Diamant (The Time of the Doves)—the story of an ordinary woman who happens to survive the extraordinary years of a war. A few years later Rodoreda finishes El carrer de les Camèlies (Camellia Street). 1966. Rodoreda is fifty-eight years old.

When I first arrive in Barcelona in the spring of 1983, Rodoreda is dying, but I don’t know she exists. It will be years till I meet the Texas parking lot attendant who first pronounces her name for me. I’m wandering the streets of Barcelona without enough money to eat. I spend the day looking for Gaudí buildings, walking instead of riding the bus to save money. When I have seen all the Gaudí I can manage, I buy the train ticket back to the French-Italian border where I live. I have enough pesetas left to buy a roasted chicken. On the train ride back, I devour that bird like a crazy lady.

May of 1992, the spring before the Olympics. It’s Sunday. I’m in Barcelona again, this time to promote one of my books. I’m staying at a hotel on las Ramblas. This time I don’t have to go without eating. My meals arrive on a shiny tray with linen folded into stiff triangles and bright silverware and a waiter who opens his arm like a magician.

“I want to go here,” I say, pointing on the map to la Plaça de la Font Castellana where Camellia Street begins or ends.

“There?” the taxicab driver says. “But there’s nothing there.”

“It doesn’t matter, that’s where I want to go.”

We drive past shop windows and leafy boulevards, apartment buildings sprouting graceful iron balconies and into Gràcia, the neighborhood of Rodoreda’s stories. But when we arrive finally at la Plaça de la Font Castellana, I realize the taxicab driver is right. There’s nothing here but a noisy rotary, a swirl of automobiles and chain-link fence, the park below under construction.

Is this la calle de las Camelias? The buildings boxlike and ugly, walls a nubby gray like a dirty wool sweater. On one corner a plaque verifies “Carrer de les Camèlies.” There aren’t many gardens left anymore. Hardly one. Did they destroy them all in the war?

Pinched between two ugly buildings, a small one-family house from the time of before, something like the house of my grandmother in Tepeyac—several potted plants, a stubborn rosebush, but no camellias. I stand outside the gate peering in like someone trying to remember something. I’ve arrived too late.

When I can’t bear the noise of Camellia Street anymore, the stink of cars and buses and trucks, I duck down a side street, zigzagging my way the several blocks to la Plaça del Diamant.

It’s nothing like I’d imagined. Bald as a knuckle, funny looking as the Mexico City zócalo. Tall apartment buildings hold up the little handkerchief of sky. Light—milky as an air shaft. Were there once trees here, do you suppose? Air throbbing with children and motorbikes, goofy teenagers hitting and then hugging each other, schoolgirls on the brink of brilliant catastrophes.

In one corner of the plaza, almost unnoticeable, as dark and discolored as the sad bronze-colored buildings, a bronze sculpture of a woman with doves taking flight—Rodoreda or Colometa, perhaps? Somebody has drawn a penis on her lower torso. Whose kid did this? A dog has left three small turds at the pedestal. Two children race round and round the sculpture giddy and growling like tigers, and I remember the joy of being chased around the statue of some green somebody—Christopher Columbus?—in Chicago’s Grant Park when I was little.

I’ve brought my camera, but I’m too shy to take a picture. I choose a park bench next to a grandmother singing and rocking a baby in a stroller. When I don’t want people to notice th

at I’m looking at them, I start writing and it makes me invisible.

Querido agridulce amargura de mis amores,

I’ve walked from el carrer de les Camèlies looking for Rodoreda. Here I am in the famous Plaça del Diamant filled with kids and motorbikes and teenagers and abuelitas singing in a language I don’t understand.

And now the boys’ soccer game has just begun. A fleet of mothers with babies on their wide hips sail past. A girl with long pony limbs and a camera is shouting “Uriel” to Uriel, who won’t turn around to have his picture taken. Somebody’s little one in a stroller stares at me like the wise guy he is until out of view. A tanned mother, plump as a peach, is being a good sport and playing Chinese jump rope with her girls. The soccer ball thuds on my notebook, knocking the pen from my hand. The one with a crooked grin and teeth too big for his mouth arrives with my pen and a shy “perdón.”

Everyone little and big is outdoors, exiled or escaped from the cramped apartments of I-can’t-take-it-anymore. All of Barcelona here at some age or another to hide or think or pull the plastic caterpillar with the striped whirligig, to kiss or be kissed where the mother won’t see them. I think of the park near my mother’s house in Chicago, how she can’t go there, afraid of the drug dealers. I think of the Los Angeles riots of a few weeks ago. How the citizens of Barcelona own their streets. How they wander fearless in their neighborhoods, their plaza, their city.

I’ve come looking for Rodoreda, and some part of her is here and some part isn’t…

“What is it about Rodoreda that attracts you to her?” a Catalan journalist will ask. I fumble about like one of Rodoreda’s characters, as clumsy with words as a carpenter threading a needle.

Rodoreda writes about feelings, about characters so numbed or overwhelmed by events they have only their emotions as a language. I think it’s because one has no words that one writes, not because one is gifted with language. Perhaps because one recognizes wisely enough the shortcomings of language.

It is this precision at naming the unnameable that attracts me to Rodoreda, this woman, this writer, hardly little, adept at listening to those who do not speak, who are filled with great emotions, albeit mute to name them.

The House on Mango Street’s Tenth Birthday

Where was I in November 1993 when I wrote this? I hardly remember. I’d bought my first house the year prior. The porch roof needed fixing, and my desk chair needed a replacement cushion. I was writing Caramelo full-time like a woman adrift at sea with only the stars for guidance. Foremost in my mind causing my compass to flounder was the deadline.

I never work well with anything that requires time management: cooking, for example, and least of all book projects. How can one predict how long a book will take to be born? And what a big breech baby Caramelo was turning out to be.

When I put my novel aside to write this introduction, I thought I could answer the most frequently asked questions from my young readers once and for all, and that would be that. But maybe young readers don’t read introductions. The questions come back again and again.

I hope the following selection will allow readers to understand I’m all my characters. And I’m none of my characters. I can write a truth only if I get out of the way and disappear. And from this Houdini trick, amazingly enough, I reappear. Without intention.

The twenty-fifth-anniversary introduction to Mango Street is also included in this collection. See this page.

It’s ten years since The House on Mango Street was first published. I began it in graduate school, the spring of 1977, Iowa City. I was twenty-two years old.

I’m thirty-eight now, far from that time and place, but the questions from readers remain: “Are these stories true?” “Are you Esperanza?”

When I started The House on Mango Street, I thought I was writing a memoir. By the time I finished, my memoir was no longer memoir, no longer autobiographical, and had evolved into a collective story peopled with several lives, from my past and present, placed in one fictional time and neighborhood—Mango Street.

For me, a story is like a Giacometti sculpture. The farther away it is, the clearer I can see it. In Iowa City, I was going through too many changes. For the first time I was living alone, in a community different in class and culture from the one where I was raised. This caused me so much distress, I could barely speak, let alone write about it. The story I was living in my early twenties would have to wait, but I could tell the story of an earlier place, an earlier voice in my life, and record this on paper.

I found my voice the moment I realized I was different. This sounds pretty simple, but until Iowa City, I assumed the world was like Chicago, made up of people of many cultures and classes all living together—not happily all the time, but still coexisting. In graduate school, I was aware of feeling like a foreigner each time I spoke. But this was my land too. This isn’t to say I’d never felt this “otherness” before in Chicago, but I hadn’t felt it as deeply. I couldn’t articulate what was happening then, except I knew when I spoke in class I felt ashamed, so I chose not to speak.

My political consciousness began the moment I could name this shame. I was in a graduate seminar on memory and the imagination. The books assigned were Vladimir Nabokov’s Speak, Memory, Isak Dinesen’s Out of Africa, and Gaston Bachelard’s The Poetics of Space. I enjoyed the first two but, as usual, said nothing, just listened to my classmates, too afraid to speak. The third book, though, left me baffled. I didn’t get it. Maybe I wasn’t as smart as everyone else, I thought, and if I didn’t say anything, maybe no one else would notice.

The conversation, I remember, was about the house of memory, the attic, the stairwells, the cellar. Attic? Were we talking about the same house? My family lived upstairs for the most part, because noise traveled down. Stairwells reeked of Pine-Sol from the Saturday scrubbing. We shared them with the tenants downstairs: public zones no one thought to clean except us. We mopped them, all right, but not without resentment for cleaning other people’s filth. And as for cellars, we had a basement, but who’d want to hide in there? Basements were filled with rats. Everyone was scared to go in there, including the meter reader and the landlord. What was this guy Bachelard talking about when he mentioned the familiar and comforting house of memory? It was obvious he’d never had to clean one or had to pay the landlord rent for one like ours.

Credit 16.1

1525 North Campbell Street, Humboldt Park neighborhood, in Chicago, the model for The House on Mango Street; my room was the one above the door.

Then it occurred to me that none of the books in this class, in any of my classes, in all the years of my education had ever discussed a house like mine. Not in books or magazines or film. My classmates had come from real houses, real neighborhoods, ones they could point to, but what did I know?

I went home that night and realized my education had been a lie—had made presumptions about what was “normal,” what was American, what was of value. I wanted to quit school right then and there, but didn’t. Instead, I got mad, and anger when it’s used to act, when used nonviolently, has power. I asked myself what I could write about that my classmates couldn’t. I didn’t know what I wanted exactly, but I did have enough sense to know what I didn’t. I didn’t want to sound like my classmates; I didn’t want to keep imitating the writers I’d been reading. Their voices were right for them but not for me.

Instead, I searched for the ugliest subjects I could find, the most unpoetic, slang, monologues where waitresses or kids talked their own lives. I was trying as best I could to write the kind of book I’d never seen in a library or in a school, the kind of book not even my professors could write. Each week I ingested the class readings, and then went off and did the opposite. It was a quiet revolution, a reaction taken to extremes maybe, but it was out of this negative experience that I found something positive: my own voice.

Mango Street is based on the speech of the Chicago streets where I grew up. It’s an anti-academic voice—a child’s voice, a gir

l’s voice, a poor girl’s voice, a spoken voice, the voice of an American Mexican. It’s in this rebellious realm of anti-poetics that I tried to create a poetic text, with the most unofficial language I could find. I did it neither ingenuously nor naturally. It was as deliberate to me as if I were tossing a Molotov.

At one time or another, we’ve all been made to feel the other. When I teach writing, I tell the story of the moment of discovering and naming my otherness. It’s not enough to simply sense it; it has to be named, and then written about from there. Once I could name it, I wasn’t ashamed or silent. I could speak up and celebrate my otherness as a woman, a working-class person, an American of Mexican descent. When I recognized the places where I departed from my neighbors, my classmates, my family, my town, my brothers, when I discovered what I knew that no one else in the room knew, and spoke it in a voice that was my voice, the voice I used when I was sitting in the kitchen, dressed in my pajamas, talking over a table littered with cups and dishes, when I could give myself permission to speak from that intimate space, then I could talk and sound like myself, not like me trying to sound like someone I wasn’t. Then I could speak, shout, laugh from a place that was uniquely mine, that was no one else’s in the history of the universe, that would never be anyone else’s, ever.

I wrote these stories that way, guided by my heart and by my ear. I was writing a novel and didn’t know I was writing a novel; if I had, I probably couldn’t have done it. I knew I wanted to tell a story made up of a series of stories that would each make sense if read alone, or that could be read all together to tell one big story, each story contributing to the whole—like beads in a necklace. I hadn’t seen a book like this before. After finishing my book, I would discover story-cycle novels later.

Have You Seen Marie?

Have You Seen Marie? Woman Hollering Creek: And Other Stories

Woman Hollering Creek: And Other Stories The House on Mango Street

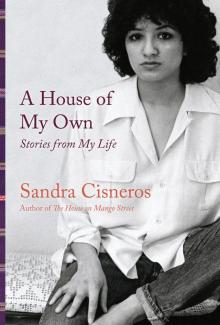

The House on Mango Street A House of My Own: Stories From My Life

A House of My Own: Stories From My Life Loose Woman

Loose Woman Caramelo

Caramelo Martita, I Remember You/Martita, te recuerdo

Martita, I Remember You/Martita, te recuerdo A House of My Own

A House of My Own My Wicked Wicked Ways

My Wicked Wicked Ways