- Home

- Sandra Cisneros

A House of My Own Page 9

A House of My Own Read online

Page 9

Repeat after me—

I can live alone and I love to…

What a crock. Each week, the ritual grief.

That decade of the knuckled knocks.

I took the crooked route and liked my badness.

Played at mistress.

Tattooed an ass.

Lapped up my happiness from a glass.

It was something, at least.

I hadn’t a clue.

What does a woman

willing to invent herself

at twenty-two or twenty-nine

do? A woman with no who nor how.

And how was I to know what was unwise.

I wanted to be writer. I wanted to be happy.

What’s that? At twenty. Or twenty-nine.

Love. Baby. Husband.

The works. The big palookas of life.

Wanting and not wanting.

Take your hands off me.

I left my father’s house

before the brothers,

vagabonded the globe

like a rich white girl.

Got a flat.

I paid for it. I kept it clean.

Sometimes the silence frightened me.

Sometimes the silence blessed me.

It would come get me.

Late at night.

Open like a window,

hungry for my life.

I wrote when I was sad.

The flat cold.

When there was no love—

new, old—

to distract me.

No six brothers

with their Fellini racket.

No mother, father,

with their wise I told you.

I tell you,

these are the pearls

from that ten-year itch,

my jewels, my colicky kids

who fussed and kept

me up the wicked nights

when all I wanted was…

With nothing in the texts to tell me.

But that was then.

The who-I-was who would become the who-I-am.

These poems are from that hobbled when.

Who Wants Stories Now

I delivered this speech about my friend Jasna the same day I wrote it, March 7, 1993, for an International Women’s Day rally in a park in downtown San Antonio, Texas. I’d lived in Sarajevo before the 1984 Winter Olympics, and the topic in the news that season was the Yugoslav war and the rape of Bosnian women. I hadn’t talked about my time there or my friend still living in Sarajevo, because I felt guilty I couldn’t do anything. But when I was invited to speak at the rally, I accepted, even though I was clueless what I could possibly say. The night before I remember fumbling about my library looking for inspiration when a book Jasna had given me fell off the bookshelf. It was a book by the Vietnamese Buddhist monk Thich Nhat Hanh, Being Peace.

I remember reading my speech at the rally and being surprised midway by my own tears. Because I didn’t want to be defeated by my emotions, I started shouting the text like a crazy lady, and my words bounced and reverberated across the Texas buildings. Afterward, I just wanted to dart off and hide, but several women came up to me and offered to sit with me at a weekly peace vigil. This was something I could do. In the next few days, I learned that The New York Times would reprint my article in their op-ed pages on March 14, 1993, and finally National Public Radio in the spring of 1994 performed my story and a letter Jasna subsequently wrote to me from war-torn Sarajevo (“Two Letters”). I moved from a place of powerlessness to action. Doing something, however small, is what Thich Nhat Hanh taught me then and continues to teach me whenever I feel I can’t possibly make a difference.

Nema. There isn’t any. Nema. It was the first word I learned when I crossed the border into Yugoslavia in 1983. Nema. Toothpaste?—Nema. Toilet paper?—Nema. Coffee?—Nema. Chocolate?—Nema. But yes, plenty of roses when I was there, plenty of war memorials to fallen partisans and mountains screaming “TITO” in stone.

It’s true. I lived there on ulica Gorica, with that man Salem, the printer, in the house that used to be the grocery. There, behind the garden wall of wooden doors nailed together. That was the summer I spent being a wife. I washed Turkish rugs till my knees were raw. I washed shirts by hand. With a broom and a bucket of suds I scrubbed the tiles of the garden each morning from all the pigeon droppings that fell from the flock that lived on the roof of the garden shed. It was summer. Everything was blossoming. Our dog Leah had fourteen puppies. The children in the neighborhood came in and out the garden gate. The garden was filled with walnuts and fruit and roses so heavy they drooped.

Jasna at her house in Sarajevo, 1983

Credit 13.2

Jasna and me, Austin, Texas, 1984

And you lived across the street, Jasna Karaula. In the house that was once your mother’s, and before her, her mother’s.

I have your recipes for fry bread, for your famous fruit bread, “It always turns out good,” you said, your rose bread, “Sometimes it turns out good.” You were filled with potted begonias and recipes and sewing and did all the amazing domestic chores I couldn’t/can’t do. You’re difficult. You smoke too much and are terribly moody. I knew you that summer before your divorce, that summer before the Winter Olympics. That afternoon I met you on the wooden bench outside the summer kitchen of our garden, and in that instant when I looked at you, when you looked at me, it was as if you’d always known me, as if I’d always known you. Of that we were convinced.

After I meet you, I’m always to be found across the street at your house, helping you fold the wash, or talking with you while you iron, or keeping you company when you lay out a dress pattern, or helping you whitewash the walls of your house that was once your grandmother’s, and then your mother’s, and then yours. You would come to the United States to visit me, to Austin, Chicago, Berkeley, San Antonio, and begin translating my stories into Serbo-Croatian. We were just getting the stories published in Sarajevo when that damn war ruined everything. Who wants stories now? There’s no shortage of stories when there’s no heat, or bread, or water, or electricity. Nema, nema, nema.

The little watercolors I painted for you, the photos of us hiking the Sarajevo mountains, the letters about the divorce, the abortion, the lace embroidered curtains, the flowered tablecloth you made by hand, your grandmother’s house on ulica Gorica, number 26, with its thick stone walls and deep-set windows, its dust, its forever need of repair, the one your father helped you fix, the one where you wedded and divorced a husband, the house where I made you a piñata and we celebrated your birthday and joked it was the only piñata to be had in all of Yugoslavia. Remember the afternoons of kaffa, roasted in the garden, served in thimble-sized cups, the Turkish way. The minarets and the sad call to prayer like a flag of black silk fluttering in the air.

Jasna. It’s ten years since that summer I lived on ulica Gorica with Salem’s family. I haven’t heard from you since last summer. When I was in Milano, you called my hotel, left a number for me to call you, but it was too late already. The lines were impossible by then, the war already begun in Sarajevo. The war you said would never reach Sarajevo.

When there was still time, you didn’t leave. Now I hear you won’t leave. Your mother sick, too frail no doubt to travel, your sister Zdenka never strong enough to even make a decision. I imagine it’s you who is taking care of them both. I’m certain of this.

In a letter that reached me by way of London, you write, “Ask your government to stop sending us ‘humilitarian’ aid. We need water, electricity, birds and trees, we need this horrible killing to stop, now, immediately, because long time ago it has been too late.”

Is it too late already, Jasna? I’m told your house has been damaged. What does that mean? Are you living in the first floor because the second floor is gone? Is the roof open to the sky? Is there still a roof? Can you sleep there in that darkness, in this winter cold ringed by mountains as tall, as icy as the Alps? A town famous for i

ts snow and mountains. I was there the summer before the Winter Olympics. And you said the houses of Sarajevo were cold in winter, even then when there was no war, when there was fuel. How must it be now, in March, when spring is still so far away, when there is no fuel to be had, how must you be managing?

I’ve talked to your sister Veronika in Slovenia. I’ve talked to your brother Davor in Germany. We light our candles and are sick with worry. I dreamt you, Jasna Karaula. You’re not dead. Not yet. I can say this with certainty, because I know you too well, and if you died, you’d come and tell me. That’s how it is between us. That’s how it’s always been.

And you haven’t visited me in a dream except to have coffee. In the last dream, we drank kaffa together in broken cups, broken because of the war I understood. I remember I held you and hugged you before waking as if we were saying goodbye until the next dream. Jasna, I’m afraid.

I’m afraid I’m not capable of saving you. I know those streets of Sarajevo. This war is not far away. This war is happening on ulica Gorica where I lived, where you live, in the house on the top of the hill, number 26. I can walk there in my mind, I know the way. I’ve been inside the minarets, the churches, the cafés. I know this town. I know your house. I’ve heard the evening prayer call and watched the devout kneel on their prayer rugs all facing Mecca, the single star and crescent moon of the Muslim graves, the Cyrillic script of the Orthodox church with its golden domes, the candles of the Catholic church of the Croatians, I’ve been there. I’ve sat at your table, raised a glass of slivovitz, toasted to your country and mine, drunk kaffa in toy-sized cups.

This is real. I’m not making this story up for anyone’s amusement. A woman is there. She’s my friend, take my word for it. That city, those streets, those houses. Where I washed rugs and scrubbed floors and gave away puppies and had coffee in the open cafés on Titograd Street. Look, what I’m trying to say is my friend is missing. This is a city where cherry trees blossomed the summer I was there, if you go to the American library on the banks of the Miljacka River, there is a copy of T. S. Eliot’s poems with one page stained with a cherry that fell from a tree while I was reading it, I’ll show you the page. I picked walnuts for the cake you made in a summer that was ripe and abundant with fruit and peace and hope, the upcoming Olympics on the horizon.

A woman is there. In the old part of the town, up the hill, up too many steps, in the neighborhood nearest the Gypsy borough, on ulica Gorica, number 26. It’s the second house from the corner, on the right, after ascending the steps. That house was once her grandmother’s, and then her mother’s, and then hers.

Mr. President of the United States, leaders of every country across the globe, all you politicians, all you deciding the fates of nations, your excellencies of power, the United Nations, dear Mr. Prime Minister, querido Señor Presidente, Mr. Radovan Karadžić, Mr. Alija Izetbegović, Mr. Cyrus Vance, Lord David Owen, fellow citizens, human beings of all races, I mean you listening to me and not listening, Dear To Whom It May Concern, God, Milošević, Pope John Paul, Clinton, Mitterrand, Kohl, all the nations of the planet Earth, my friends, my enemies, my known and unknown ancestors, my fellow human beings, I’ve had it with all of you.

She’s in there. Get her out, I tell you! Get her out! Get them out! They’re in that city, that country, that region Bosnia Herzegovina, there in that oven, that mouth of hell, that Calvary, that Dachau, that gas chamber, that Chernobyl, that holocaust, that house on fire, get her out of there, I demand you.

I demand you march, take a plane, better take a tank. Take some of these blankets I have, my beautiful new home, my lovely silk suits, my warm stockings, my full belly, my refrigerator with things to eat, my supermarket, my spring weather, my electricity, my clean water, my pickup truck, my U.S. dollars, my trees and flowers and nights soundless and whole.

I demand you go right in there. I demand you give me a sword mightier than this useless pen of mine. I demand you arrive in Sarajevo. I’ll take you to ulica Gorica, I’m afraid, but I’ll take you. Spirits of all you deceased relatives and friends, my ancestors, my compatriots, fellow human beings, I demand, I ask, I beg you.

In the name of civilization. In the name of humanity. In the name of compassion. In the name of respectability. In the name of mankind. Bring that woman out of there. That woman, hermana de mi corazón, sister of my heart. I know this woman. I know her mother, I know her sister as well. They’re in that city. In that awful place that was once so peaceful a woman could walk alone at night unafraid.

About words. I know what my demands mean. I know about words. I’m in the business of words. There’s no shortage of words in Sarajevo. I’m a writer. I’m a woman. I’m a human being. In other wars I remember watching Buddhist priests set themselves on fire for begging for no less than what I ask for, and what good did it come to?

A woman I know is in there. In that country. A woman I love as any woman would love a woman. And I am in San Antonio, Texas, and the days and the hours and the months pass and the newspapers cry, “Something must be done!” Somebody, someone, help this somebody.

And I hear that somebody. And I know that somebody. And I love that somebody. And I don’t know what to do. I don’t know what to do.

La Casa Que Canta

Credit 14.1

When I met the photographer Mariana Yampolsky, I was looking for a way to be an artist and to love someone. Now at fifty-nine I feel quite content and whole just as I am. I love writing, I live alone—if one can call five dogs alone—and I am perfectly at ease as a pond of water. I desire nothing. Except a house. And, on a regular basis, a box of salted French caramels.

I need to mention that I began this piece well before Mariana’s death in 2002, but was prompted to resurrect and finish it on April 1, 2003, for a San Francisco exhibit in Mariana’s honor.

During the New Year of 1985, a snowstorm arrived in South Texas that fell so hard all of San Antonio shut down and pipes burst. I was away for the holidays and came back to the city and my apartment to find my books had been soaked with water. At that time I couldn’t afford bookshelves, and my books sat on the floor. To add grief to sorrow, I remember finding my finest treasure, a Mariana Yampolsky book, destroyed by the flood. It was La Casa Que Canta, the house that sings, its pages as wavy as if someone had cried a thousand tears upon them.

I spent the rest of the night ironing my books, the apartment steamy as a dry cleaners, as determined to save my treasures as any art historian saving Florence. It wasn’t the best restoration job, but it would have to do. La Casa Que Canta had been published in a limited edition and was already out of print.

I have often returned to that book, to draw inspiration, to remind myself what it is that captivates me about Mariana, about Mariana’s houses, about Mexican houses in particular. To Mariana, the more humble the house, the more splendid, something to be looked at with respect and awe. She documented the homes that would never be featured in the glossy pages of House & Garden. These were houses where floors were pounded silky by bare feet, architecture where everything had the unmistakable air of being made by hand, homes forgotten in the countryside and dusty towns, full of duende. The arabesque of a hinge. A door made of dried organ cacti. Deep-set windows like eyes. A porch with two flowered chairs snoozing in the half-sun. A kitchen wall splendid with enamel pots and dishes. A hammock, a hat, a crib hanging from a house beam. A tortilla toasting on a comal.

Mariana and Arjen, at my house

Several years later, I finally replaced that ripply La Casa Que Canta with a clean copy found in a rare bookstore in downtown Mexico City. By then I had acquired a house of my own finally, and, at long last, bookshelves.

Mariana Yampolsky and her husband, Arjen van de Sluis, came to San Antonio just at this point in my life. I immediately invited them to my house, seated them on my couch for a photo portrait, and admired them shamelessly. I entertained Mariana with the story of my original La Casa Que Canta and made her sign my new copy. She wrote—“¡tu

casa es muy muy bonita! ¡tú eres bonita! ¡y lo que escribes más!”

Whenever Mariana spoke, Arjen looked at her with the sincere adoration of a man made foolish by love. For her part, Mariana treated him with the diffidence and annoyance of an only child or a pampered Pekingese.

The photo I took of them is somewhere, who knows where, but I remember it looked like this: two leaning into each other like houses slouched with time, and, like it or not, in love, after everything and always.

It occurred to me that this couple had the secret to what I was looking for. I asked how was it they had remained together so successfully for so many years when all my own loves had never lasted as long as my toaster. What was the secret of being an artist—I meant, of course, a woman artist—and keeping a man?

“Respect,” Arjen replied. “For what you each do.”

“Ah, is that it?”

“Yes,” he said, and I seem to remember Mariana nodding.

They rose to leave, and Mariana invited me to their house in Tlalpan, on the southern edge of Mexico City. “Soon,” I said, without knowing that the book I was writing would delay that “soon” to “nunca.”

“Hasta pronto,” Mariana said, which translates literally as “until soon,” but means “until later.”

“Goodbye,” we each said. “Goodbye, goodbye.” As lazily and luxuriously as if we were in control of our own destinies.

Mercè Rodoreda

Credit 15.1

I often remember where I was when meeting a book that sweeps me off my feet. I remember the moment and the intimate sensation of devouring a beloved text as distinctly as I recall the most sensual encounters of my life. Is it like this for everyone, or is it like this only for those who work with words?

Have You Seen Marie?

Have You Seen Marie? Woman Hollering Creek: And Other Stories

Woman Hollering Creek: And Other Stories The House on Mango Street

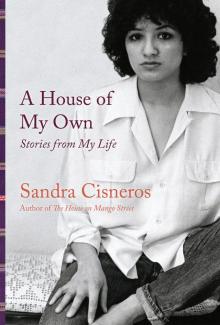

The House on Mango Street A House of My Own: Stories From My Life

A House of My Own: Stories From My Life Loose Woman

Loose Woman Caramelo

Caramelo Martita, I Remember You/Martita, te recuerdo

Martita, I Remember You/Martita, te recuerdo A House of My Own

A House of My Own My Wicked Wicked Ways

My Wicked Wicked Ways