- Home

- Sandra Cisneros

A House of My Own Page 8

A House of My Own Read online

Page 8

All this I thought while the guy in front of me was getting his flyer signed. And now it was my turn, and Astor Piazzolla in his black trousers with their sharp creases, in his silky black shirt and polished black boots, Astor with only his hands and face illuminating the moment, was reaching out and taking my flyer from my hand. I stood there with my mouth open a little.

Now as he signed I needed to tell him. It was my chance, yes. I could say it now. I could tell him. Now!

“Señor Piazzolla,” I said breathlessly. “Your work. Is. My life!”

He nodded, passed my flyer on down the line to his fellow musicians to sign, and then…

My moment was gone.

I clenched that autographed flyer in one fist and wobbled back to my seat feeling foolish and weepy. Your work is my life! What was I thinking?

Then I put my head down to write. “Thing in my shoe, / dandelion, thorn, thumbprint, / one grain of grief that has me undone once more, / oh my father, heartily sorry I am for this right-side of the brain / who has alarmed and maimed and laid me many a day now invalid low.” And when I raised my head, I had a new book of poetry. Just as if I’d gone through childbirth, my body changed, startling me with flesh where I’d once had bone. I put my head down again, and again when I raised it, another book, and again my body altered, so that I was no longer myself, but a woman staring at a woman from the other side of water. Books and more books, and more changes to the house one calls the self.

Young people get in line to meet the author and have their book autographed. I am the author they’ve come to meet. Some of them barely able to talk, their eyes like ships lost at sea.

“You don’t know what this means to me,” they say, fumbling with the page they want me to sign. “You just. You just don’t know.”

Only Daughter

In the year of my near death, 1987, I was sick over a ten-month period. Had I been ill with something physically visible, I might’ve known to run and see a doctor. But when we are sick in the soul, it takes a long time to realize a spirit wound that won’t heal is equally as dangerous as a flesh wound that can’t.

The following was written in 1989 as I was rising from that dark night. It overwhelmed me then and overwhelms me now to realize the timing of these accolades; they could’ve arrived posthumously. I’ve learned since then that despair is part of the process, not the destination.

Once, several years ago, when I was just starting out my writing career, I was asked to write my own contributor’s note for a literary anthology. I wrote, “I am the only daughter in a family of six sons. That explains everything.”

Well, I’ve thought about that ever since, and yes, it explains a lot to me, but for the reader’s sake I should have written, “I am the only daughter in a Mexican family of six sons.” Or even: “I am the only daughter of a Mexican father and a Mexican American mother.” Or: “I am the only daughter of a working-class family of nine.” All of these had everything to do with who I am today.

I was/am the only daughter and only a daughter. Being an only daughter in a family of six sons forced me by circumstance to spend a lot of time by myself because my brothers felt it beneath them to play with a girl in public. But that aloneness, that loneliness, was good for a would-be writer—it allowed me time to think and think, to imagine, to read and prepare myself for my writer’s profession.

Being only a daughter for my father meant my destiny would lead me to become someone’s wife. That’s what he believed. But when I was in the fifth grade and shared my plans for college with him, I was sure he understood. I remember my father saying, “Qué bueno, mi’ja”—that’s good. That meant a lot to me, especially since my brothers thought the idea hilarious. What I didn’t realize was that my father thought college was good for girls—good for finding a husband. After I finished four years of college and two more in graduate school, and still no husband, my father shakes his head even now and says I wasted all that education.

In retrospect, I’m lucky my father believed daughters were meant for husbands. It meant it didn’t matter if I majored in something silly like English. After all, I’d find a nice professional eventually who might marry me, right? This allowed me the liberty to putter about embroidering my little poems and stories without my father interrupting with so much as a “What’s that you’re writing?”

But the truth is I wanted him to interrupt. I wanted my father to understand what I was scribbling, to introduce me as “My only daughter, the writer.” Not as “This is my only daughter. She teaches.” “Es maestra” were his exact words. Not even “profesora.”

In a sense, everything I have ever written has been for him, to win his approval even though I know my father can’t read English words. My father’s only reading includes Mexican comic books—La Familia Burrón, his chocolate-ink Esto, a Mexican sports magazine, or fotonovelas, little picture paperbacks with tragedy and trauma erupting from the characters’ mouths in bubbles. My father represents, then, the public majority. A public who is uninterested in reading, and yet one whom I’m writing about and for, and privately trying to woo.

When we were growing up in Chicago, we moved a lot because of my father. He suffered bouts of nostalgia. Then we’d have to let go our flat, store the furniture with Mother’s relatives, load the station wagon with baggage and bologna sandwiches, and head south. To Mexico City.

We came back, of course. To yet another Chicago flat, another Chicago neighborhood, another Catholic school. Each time, my father would seek out the parish priest in order to get a tuition break, and complain or boast, “I have seven sons.”

He meant siete hijos, seven children, but he translated it as “sons.” “I have seven sons,” he would say to anyone who would listen. The Sears employee who sold us the washing machine. The short-order cook where my father ate his ham-and-eggs breakfasts. “I have seven sons.” As if he deserved a medal from the state.

Our family en route to Mexico City, c. 1964; I am seated on my mother’s right.

My papa. He didn’t mean anything by that mistranslation, I’m sure. But somehow I could feel myself being erased. I’d tug my father’s sleeve and whisper, “Not seven sons. Six! And one daughter.”

When my oldest brother graduated from medical school, he fulfilled my father’s dream that we study hard and use this, our head, instead of these, our hands. Even now my father’s hands are thick and yellow, stubbed by a history of hammer and nails and twine and coils and springs. “Use this,” my father said, tapping his head, “and not this,” showing us those hands. He always looked tired when he said it.

Wasn’t college an investment? And hadn’t I spent all those years in college? And if I didn’t marry, what was it all for? Why would anyone go to college and then choose to be poor?

Last year, after ten years of writing professionally, the financial rewards started to trickle in—my second National Endowment for the Arts fellowship; a guest professorship at the University of California, Berkeley; my book sold to a major New York publishing house.

At Christmas, I flew home to Chicago. The house was throbbing, same as always: hot tamales and sweet tamales hissing in my mother’s pressure cooker, and everybody—my mother, six brothers, wives, babies, aunts, cousins—talking too loud and at the same time, because that’s just how we are.

I went upstairs to my father’s room. One of my stories had just been translated into Spanish and published in an anthology of Chicano writing, and I wanted to show it to him. Ever since he recovered from a stroke two years ago, my father likes to spend his leisure hours horizontally. And that’s how I found him, watching a Pedro Infante movie on television and eating rice pudding.

There was a glass filmed with milk on the bedside table. There were several vials of pills and balled Kleenex. And on the floor, one black sock and a plastic urinal that I didn’t want to look at, but looked at anyway. Pedro Infante was about to burst into song, and my father was laughing.

I’m not sure if it was because my story

was translated into Spanish, or because it was published in Mexico, or perhaps because the story dealt with Tepeyac, the colonia my father was raised in and the house he grew up in, but at any rate, my father punched the Mute button on his remote control and read my story.

I sat on the bed next to my father and waited. He read it very slowly. As if he were reading each line over and over. He laughed at all the right places and read lines he liked out loud.

He pointed and asked questions, “Is this so-and-so?”

“Yes,” I said. He kept reading.

When he was finally finished, after what seemed like hours, my father looked up and asked, “Where can we get more copies of this for the relatives?”

Of all the wonderful things that happened to me last year, that was the most wonderful.

Letter to Gwendolyn Brooks

I once ran into Gwendolyn Brooks in the basement of the Stop & Shop in downtown Chicago. This was when she knew me as a high school teacher and not as a writer. She was standing in line at the bakery counter looking like a mother coming home from work.

“Miss Brooks, what are you doing here?”

“I’m buying a cake,” Miss Brooks said matter-of-factly.

Of course she was buying a cake. Still, it didn’t seem possible then that poets of her stature went downtown on the subway and bought themselves cakes. Gwendolyn Brooks was famous, maybe the most famous person I knew then, and I admired her greatly. I’d been reading her work since high school. To meet her at a university or bookstore was one thing. But here she was waiting to buy a cake! She didn’t look like a Pulitzer Prize–winning author. She looked like a sparrow or a nun in the modest brown and navy she always wore.

Like Elena Poniatowska, she taught me what it is to be generous to others, to speak to every member of your public as if they were the guest writer, and not the other way round.

This generosity and way of honoring her readers has made me see her not only as a great poet but as a great human being, and this, in my book, is the greatest kind of writer of all.

This letter was written while I was guest professor at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque.

March 5, 1991

Dear Ms. Brooks,

It is what Winnie-the-Pooh would call a blustery day here. Or what Miss Emily would designate a wind like a bugle. From over and over the mesas, snapping dust and terrifying trees.

I am in my pajamas though it’s past midday but I like my leisure to dream a little longer when I am asleep, and continue dreaming on paper when I am awake. I am rereading your wonderful MAUD MARTHA again, a copy you gave me, and which I am very grateful to have. I remember when I first discovered that book, in the American library in Sarajevo, across from the famous river where the archduke was shot that started a world war. And it was there too that I read T. S. Eliot’s collected poems. If you go to Sarajevo and look at the chapter on PRACTICAL CATS you’ll see a cherry stain on one of the pages—because I was reading the book on the opposite bank of the river, under a row of cherry trees in front of my American friend Ana’s apartment house, and at the moment I was reading about one of Eliot’s cats—the Rum Tum Tugger?—a wind shook a cherry loose that landed with a startled plop on the page. And my heart gave a little jump too because the book wasn’t mine. A wine-colored stain against the thick creamy pages.

I mean to teach it one day along with other books that use a series of short interrelated stories. Perhaps with Ermilo Abreu Gómez’s CANEK and Nellie Campobello’s CARTUCHO albeit the translations of both are crooked. The form fascinates. And I’d done as much with MANGO STREET, though I hadn’t met your MAUD yet. Perhaps I was “recollecting the things to come.”

Ms. Brooks, please know I haven’t quite disappeared altogether from the land. I’ve been migrant professor these past years, guest writer in residence at UC Berkeley, UC Irvine, the Univ. of Michigan at Ann Arbor, and now here for one semester. All for the sake of protecting my writer self. Some years dipped low and some reeled to high heaven. But now the days are good to me. I have a new book due out from Random (see enclosed reviews), and I have sold my little house on Mango to the big house of Vintage. Both books slated for this April. And it seems my life is a whirl like the wind outside my window today. Everything is shook and snapped and wind-washed and fresh, and, yes, that is how it should be.

I only wanted to say this to you today. That your book gives me much pleasure. That I admire it terribly. I think of you often, Ms. Brooks, and your spirit is with me always.

un abrazo fuerte, fuerte,

Sandra

My Wicked Wicked Ways

Credit 12.1

The reissue of my first book of poems by Knopf in 1992 demanded commentary. After publishing them with a small press the first time, I’d felt a strange postpartum depression. We’d never talked about pro-choice regarding publishing poetry when I was a student in the graduate poetry workshop; it was assumed if you wrote poems you had to publish them, or you weren’t a real poet. A given. Like being a woman meant you had to have a child to make you a real woman. Or did you?

It seems to me the act of writing poetry is the opposite of publishing. So I made a vow to myself after that first book to choose to not publish poetry from then on. I’d say what I had to say publicly in fiction, but poems were to be written as if they could not be published in my lifetime. They came from such a personal place. It was the only way I could free myself to write/think with absolute freedom, without censorship. From then on, I’d toss them under the bed like Emily Dickinson. And for a time, that’s what I did.

When I finally moved from a little publishing house to a big one a decade later, I was reluctant to have the early book of poems reissued, but I felt that a hardback from a big New York press would help Norma Alarcón’s small press, Third Woman, which had taken a chance on me.

I was asked to write a new introduction and agreed to do so. But then, of course, writer’s block stepped in. The only way to get around my fear was to trick myself. After many false starts, I found the way to do this was by writing my introduction in verse. It was finished in June of 1992, in Greece, on the island of Hydra, the same place I’d finished The House on Mango Street ten years before. The Los Angeles Times Book Review published the poem on September 6, 1992, as “Poem as Preface.” I want to add as I relook at this poem now as a woman at the end of my fifties, I can and do enjoy living alone. And, yes, despite all my whining, I love to work.

I can live alone and I love to work.

—MARY CASSATT

Allí está el detalle. (There’s the rub.)

—CANTINFLAS

Gentlemen, ladies. If you please—these

are my wicked poems from when.

The girl grief decade. My wicked nun

years, so to speak. I sinned.

Not in the white woman way.

Not as Simone voyeuring the pretty

slum city on a golden arm. And no,

not wicked like the captain of the bad

boy blood, that Hollywood hood-

lum who boozed and floozed it up,

hell bent on self-destruction. Not me.

Well. Not much. Tell me,

how does a woman who?

A woman like me. Daughter of

a daddy with a hammer and blistered feet

he’d dip into a washtub while he ate his dinner.

A woman with no birthright in the matter.

What does a woman inherit

that tells her how

to go?

My first felony—I took up with poetry.

For this penalty, the rice burned.

Mother warned I’d never wife.

Wife? A woman like me

whose choice was rolling pin or factory.

An absurd vice, this wicked wanton

writer’s life.

I chucked the life

my father’d plucked for me.

Leapt into the salamander fire.

A girl who’d never roamed<

br />

beyond her father’s rooster eye.

Winched the door with poetry and fled.

For good. And grieved I’d gone

when I was so alone.

In my kitchen, in the thin hour,

a calendar Cassatt chanted:

Have You Seen Marie?

Have You Seen Marie? Woman Hollering Creek: And Other Stories

Woman Hollering Creek: And Other Stories The House on Mango Street

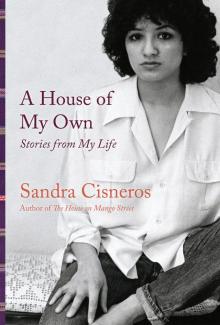

The House on Mango Street A House of My Own: Stories From My Life

A House of My Own: Stories From My Life Loose Woman

Loose Woman Caramelo

Caramelo Martita, I Remember You/Martita, te recuerdo

Martita, I Remember You/Martita, te recuerdo A House of My Own

A House of My Own My Wicked Wicked Ways

My Wicked Wicked Ways